Work began on the fourteen-screen print series based on the medieval poem, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, in late 2015, and completed in January 2018. A collaboration between me and Dan Bugg of Penfold Press, at the start of it, with no-one other than ourselves to please, we had no real schedule or deadline for completion. (We’d airily thought we might make two prints per year over seven years!) However, the project quickly gathered a momentum of its own with an offer of a first-stage exhibition at the Martin Tinney Gallery in the diary for 2017, and suddenly the pressure to work swiftly was on. Art writer and curator James Russell joined the project and began making accompanying notes for the prints. Another imperative to complete the series faster than we’d originally intended emerged last year – more news about that later – and at that point, Dan and I knew we had little option other than to strap on our skates and fly.

The following is an extract from a letter to my friend Liz Sangster, with whom I worked in a past life at the workshops of the Welsh National Opera:

“I can’t think of a more wonderful project to have worked on – but the schedule has been relentless. You’ll recall from all those years you were at WNO that sometimes when a deadline has you in its grip, you go onto autopilot. Everything you know suddenly comes into play – all the deep knowledge and expertise – and the thinking seems to stop. It’s like floating at speed as the current bears you and carries you forward, rather than thinking about how to swim. Instinct takes over. I’d thought about these images for so long that when the moment came to make them it was as though they developed, like photographs. To be perfectly honest I can’t even recall the process of drawing many of them. How weird is that?”

>>><<<

Christmas at Camelot. 2015. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

CHRISTMAS AT CAMELOT

All the joy and exuberance of Christmas at King Arthur’s court is expressed in this print, the first of a series of fourteen to be based on the medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The author of this verse saga, the mysterious Pearl Poet, is unstinting in his praise as he introduces the courtiers, equating their finery with their moral worth. In his recent translation Simon Armitage describes the two-week-long midwinter feast as ‘a coming together of the gracious and the glad: the most chivalrous and courteous knights known in Christendom’.

Elegant, innocent and noble, these lively young men and women spend the evenings carousing and the daylight hours on the jousting field. Here we see the best of the best, King Arthur and his queen Guinevere (a woman whose eyes outshine the brightest of her jewels), and beyond them Sir Gawain. The horses prance. The riders eye us coolly, not least the knight, who seems ready for any challenge.

Another artist might have chosen to introduce the series with a scene of Christmas feasting, but Clive Hicks-Jenkins’ depiction of the three riders suggests the lightheartedness and energy of the youthful court, while also emulating the airy elegance of the poem. Dan Bugg’s expert handling of colour pulls a complex, multi-layered print together, making it feel as taut and snappy as a heraldic banner unfurling in the breeze.

…

The Green Knight Arrives. 2016. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE GREEN KNIGHT ARRIVES

Arthurian legend is full of warriors, but the Green Knight is unique – unearthly, even monstrous, yet still a knight. His unexpected arrival during the Christmas feast is one of the most famous entrances in the canon of British literature, accompanied in the poem by what Clive calls a ‘forensic’ description of his outlandish appearance.

Clive looks beyond the poetry to explore the character and cultural implications of Gawain’s nemesis, in an intense portrait of mingled power and vulnerability. The upper body of the Green Knight fills the frame, his statuesque head and massive arm suggesting the might of an ancient god – but in a sensitive pose reminiscent of Rodin. That flowing beard hints at the graphic gravitas of a playing card king; look again and it is a river flowing through a tattooed forest. Our 21st century Green Knight is a modern primitive, whose identity is etched into his skin.

A fascination for the decorated body has long been a feature of Clive’s work, and here there is a powerful pictorial contrast between the blood-red towers and battlements of Camelot and the organic forms inked into the Green Knight’s skin. As he prepares to bang on the door of King Arthur’s great hall, we can’t help but notice the lopped oak tree on his raised arm. Is this a record of violence done to nature? Nothing is explicit, but much is implied in this luminous vision of contrasting cultures: medieval Christian civilisation on the one hand, and, on the other, the timeless wild.

…

The Green Knight Bows to Gawain’s Blow. 2016. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE GREEN KNIGHT BOWS TO GAWAIN’S BLOW

The contrast between martial red and forest green becomes more explicit in the third print of the series. Having accepted the Green Knight’s challenge to strike him, Gawain stands helmeted, axe raised – the very picture of a proud medieval knight. His expression is steely, yet he is staring not at his victim but straight ahead, and when we look more closely at his eyes and mouth we sense his apprehension. Honour demands that he strike the blow, but the possible consequences are terrifying. For his part, the Green Knight seems perfectly composed.

Whereas the audience in the poem is the assembled might of Camelot, the action here is observed by an unsettling pair of onlookers. To the left a carved architectural figure – Green Man as caryatid – watches wide-eyed. To the right a griffin-like creature atop a sepulchre stares grimly down at the knight, who appears caught within a triangle composed of the Green Knight and his familiars, ancient beings once petrified but now brought back to life.

The arrival of the Green Knight has transformed Camelot from gleaming medieval palace (like those immortalised in Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry) to haunted castle. Like the protagonist of a horror film who wanders into a nightmare, Gawain stands resolute but scared. He may be the one wielding the axe, but the weapon belongs to the Green Knight – and only he knows what will happen when it falls.

…

The Green Knight’s Head Lives. 2016. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE GREEN KNIGHT’S HEAD LIVES

This is the moment when we realise, beyond all doubt, that the Green Knight is a magical being. The axe has done its bloody work, severing the strange visitor’s head, but rather than fall to the ground and die the Green Knight picks up his head and holds it aloft to speak.

To the Pearl Poet’s audience this was probably quite alarming, but in the age of the horror movie and computer-generated imagery we have become more used to shock and gore. Besides, the scene itself is so well-known that the twenty-first century artist runs the risk of descending into cliché, unless they can find a new way of communicating its ghastliness. Clive spent months working on different ideas, eventually coming up with this extraordinary image.

No architectural details distract us in this close-cropped study. Calm and resolute as ever, the Green Knight holds up his head. From his neck blood doesn’t so much gush forth as billow out, in a way that is disturbing but strangely beautiful. It’s as if he taken off a mask to reveal some other alien self: a primal organic form as ornately structured as lichen, or a lung.

Equally ornate are the embroideries of the horse’s caparison, which teem with foliate curlicues, flighty peacocks and talismanic eyes – wonders of the Green Knight’s world – but it is the animal’s expression that gives the print its urgency. In a manner reminiscent of Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, the bared teeth and rolling eyes express pure terror – the terror we imagine Arthur’s courtiers felt at the Green Knight’s supernatural display.

…

The Armouring of Gawain. 2016. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE ARMOURING OF GAWAIN

A year has passed since Gawain’s first encounter with the Green Knight, and now he prepares to set off in search of his adversary, as he has sworn to do. In this portrait, designed as a pendant to ‘The Green Knight Arrives’ we see the young knight outside the walls of Camelot, alone as he must be on his quest. Gawain’s armour is magnificent, particularly the helmet with its splendid plume that flows and ripples like the Green Knight’s beard. The decorative stars and delicate tracery of foliage contrast with the robust trees and leaves with which his enemy’s skin is tattooed, reminding us that the world of Camelot exists at a remove from nature.

In the poem we learn that the front of Gawain’s shield is decorated with a five-pointed star, with each point representing a set of his virtues: the dexterity of his five fingers; the perfection of his five senses; his fidelity (rooted in his devotion to the five wounds of Christ); his reflection on the five joys of Mary in Christ; and the five knightly virtues (generosity, fellowship, chastity, courtesy and charity).

The reverse side of the shield bears a picture of Mary, depicted here. She seems to offer neither joy nor succour, but instead gazes coolly at the knight. To judge from his pallor and anxious frown, meanwhile, Gawain is terrified, too preoccupied perhaps to notice the locks of hair escaping untidily from beneath his helmet. Or perhaps they remind us that behind the shield with all its virtuous imagery a young man stands, with all a young man’s strength and weaknesses.

…

The Travails. 2016. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE TRAVAILS

Armoured but helmetless, his shield held staunchly before him, Gawain plunges his spear into the breast of a serpent. Fans of Clive’s work may recognise the grinning beast with its ghastly scaled body as a relative of the dragon battled by St George in a memorable series of paintings, but this is a different kind of image for a different kind of story. The tale of St George would have been familiar to the Pearl Poet’s original audience, as would a host of quest narratives and stories of bravery in which the slaying of a dragon or similar beast represented a culmination. Victory proved the knight’s valour and therefore his moral worth. Not so in the case of Gawain.

In one short if vivid passage we learn of his journey in search of the Green Knight’s home, the Green Chapel, in which he vanquishes a menagerie of medieval monsters. Wolves, bears, giants, woodwoses, serpents… none can match him. He proves his strength and courage again and again, but these battles are little more than ritual acts. The world has moved on, and when he undergoes his true test he will not even know he is being tested.

In portraying St George, Clive presented the sinuous form of the dragon and the limbs of the knight twisting together in violent struggle, but Gawain is not wrestling this beast. He is dispatching it, calmly and resolutely. Is it his virtuous shield with the painting of Mary that empowers him? Or is he simply too strong for mere serpents? Or are these easy victories set up for him, to inflate his pride? The falling oak leaves suggest that we are already within the Green Knight’s domain

…

Gawain Arrives at Fair Castle. 2017. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

GAWAIN ARRIVES AT FAIR CASTLE

Compare this image with the first in the series, ‘Christmas at Camelot’, and it is clear that the quest to find the Green Chapel has been the making of Gawain. Fully armoured, with a visor covering his face, he has become a figure at once powerful and flamboyant, his cloak flying behind him as he gallops along. The sinuous form of the vanquished serpent now finds an echo in the elaborate dance of the banner tied to his lance, and there on his shield is the pentangle, proof, if any were needed, of his knightly virtues.

His horse, Gringolet, also seems to have grown in stature and is now a magnificent beast, its splendid chest bursting from a beautifully decorated caparison. Everything about horse and rider trumpets their power and their glory, from the set of the animal’s tail and tremendous curved neck, to the thrust of Gawain’s leg as he rides.

And then there is Fair Castle. We learn in the text that, on Christmas Eve, half-starved and freezing, Gawain prays to Mary for help in finding a place where he might celebrate Christmas Mass. After confessing his sins and crossing himself three times he looks up to see that his prayers have been answered. There stands a beautiful castle, white and shimmering according to the poem but in Clive’s vision a splendid Byzantine edifice perched on a preposterous pinnacle – a palace conjured by sorcery. A tell-tale oak leaf flutters down, but does Gawain see it as he plunges forward?

…

The Three Hunts. 2017. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE THREE HUNTS

A historian researching medieval hunting techniques of hunting could learn a lot from the Pearl Poet’s lengthy description of the three hunts led by Bertilak, the Lord of Fair Castle. On succeeding days an entire herd of deer, a gigantic wild boar and a solitary fox are chased, dispatched with great relish, and bloodily slaughtered. This is hunting on an epic scale, gleefully and gruesomely described, and to the modern reader it comes as a shock.

Gawain himself does not take part in the hunts, but remains at Fair Castle to be entertained – he thinks – by Bertilak’s wife. In fact, as we soon realise, she is trying to seduce him, and the main role of the three hunts is to prolong the gentle torture, delaying the moment of Gawain’s fall. So how to represent them? Much earlier, while considering how to represent the Green Knight’s decapitation, Clive decided to focus on the magical quality of the scene, and he has taken a similar approach here.

Like his castle, Bertilak’s domain is a fantasy, and here we see the forest conjured out of nothingness. A phantom huntsman blows his horn, startling a white stag; a wild boar lowers its head, preparing to charge. But where is the third creature, sly Renard? He has broken into the castle garden and killed a peacock – a bird we might recognise from the caparison of the Green Knight’s horse. Blood has been spilled in the magic domain, and the fox will soon pay the price.

…

The Temptations. 2017. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE TEMPTATIONS

When we last saw Gawain he was making his triumphant approach to Fair Castle astride his magnificent steed, helmet on head and shield on arm. In this guise he has (we will remember) triumphed over medieval beasts both real and imaginary, and as far as he is concerned his sojourn at Fair Castle is just a pleasant if distracting interlude before he resumes his knightly quest.

Given what awaits him when he finds the Green Chapel we might forgive Gawain for tarrying a while, and given the warmth of his welcome it is no wonder he obeys Bertilak’s instruction to relax while the rest of the men are out hunting. We, however, have been forewarned by clues in the text, such as a reference to ‘tricks’. Gawain, we sense, is about to be tested, and now he has no armour, no shield emblazoned with the figure of Mary. We see him for the first time as a young man, athletic but vulnerable as he lies naked, his eyes closed.

Bertilak’s wife spends three days with him, testing and teasing, and almost until the end his resolve lasts. We see it in his face, this determination to be virtuous, as we see the luminous allure of his beautiful hostess. Without the third part of this tripartite design this would be a serious study of temptation, but nothing in this story is quite what it seems. Gawain, the would-be hero, is in one sense the butt of an elaborate practical joke to which we as readers are party. As he lies, eyes closed, wrestling with his conscience, he is unaware of the tapestry behind his bed, decorated with comical copulating rabbits.

…

The Exchange. 2017. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE EXCHANGE

Having evolved over many years, Clive’s vision of Gawain is very much his own. So while this set of prints follows the Pearl Poet’s narrative, the imagery and themes are not all drawn literally from the poem. Each print is a work of art in its own right, rather than an illustration, and the whole set represents a sort of coda to the poem, an echo across the ages.

According to the poem Gawain inhabits a landlocked world of mountains and forests; he travels on horseback, not by boat. But here is a ship, apparently at anchor beneath the walls of Fair Castle, where our hero and his host exchange gifts. Bertilak has returned from the hunt with a magnificent stag (its gaping chest reminding us of the mortal danger Gawain faces), while Gawain has accepted one kiss from Bertilak’s wife. This he now presents to his host, who leans down over him in his splendidly patterned jacket – a magician’s cloak?

Again we sense the knight’s youth and vulnerability as he tries to follow the rules of this strange court and to treat his host and hostess with the appropriate respect. So might the boat symbolise his desire to get away, or perhaps the sense that he is ‘all at sea’? Are there currents swirling in the ocean deep, as there are perhaps within his heart? Or is this simply a design woven into a tapestry, that forms a backdrop to the scene?

…

The Green Chapel. 2017. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE GREEN CHAPEL

When Gawain and the Green Knight last met, the former was wielding an axe over the latter’s head, and now it is time for the roles to be switched. Gawain has reached the Green Chapel, but has not yet noticed his adversary observing him coldly from afar. Then comes a dreadful sound, the sharpening of a blade, and, like the stag hearing the huntsman’s horn, Gringolet pricks up his ears.

This print is almost a dark reflection of ‘The Exchange’, with a similar use of perspective but a very different mood. Elaborate tapestries and bright colours make way for angular natural forms and the darker tones that bode ill for Gawain. A freak in Camelot with his long beard and tattooed limbs, the Green Knight is at home here. He blends in with rock and flowing water, in fact he seems at this moment to be carved from rock, like a sinister Assyrian god. His hand rests lightly on the head of the battle axe Gawain took up so bravely at Arthur’s feast, when no-one more senior would accept the challenge.

Have Arthur and his knights spared a thought for Gawain as they enjoyed this year’s winter feast? Have they pondered the fate of the young knight who has been forced, through no fault of his own, to undertake a suicide mission? Here we see in the tiny, distant figure a solitary man dwarfed by a wilderness that is remote in every way from the world he knows. An innocent who is about to become a sacrificial victim.

…

Gawain Staunches the Wound to His Neck. 2017. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

GAWAIN STAUNCHES THE WOUND TO HIS NECK

The Green Knight raises his axe to strike Gawain, but the knight shrinks from the blow. The second strike misses. The third nicks the flesh of his neck, and perceiving his salvation Gawain leaps away and demands that the Green Knight honour their bargain: a blow for a blow. The monstrous figure leans on his axe and, in a good-humoured tone, explains that Gawain has been secretly tested and that he has passed with flying colours. His only fault – which earned him the wound to his neck – lay in accepting the girdle from Bertilak’s wife and not revealing the gift to his host.

This we might think is an innocuous crime. Certainly Bertilak – for the Green Knight is he – considers Gawain the most honourable of men in spite of his lapse. But the proud young knight sees the situation very differently, and this print captures beautifully his horror and his shame. In the intense moment of realisation everything disappears in a burst of white light, leaving even the Green Knight a phantom. Crop-headed suddenly, and with the harrowed features of a seasoned soldier, Gawain stares down at his proud plumed helmet, from which foliate pattern bursts forth. It is appearing on his armour too, the grand armour which now seems to imprison his pale flesh.

From his neck the girdle flies upward and back, as if blown by the wind. But this animation, like everything else Gawain has encountered since the story began, is the work of magic.

…

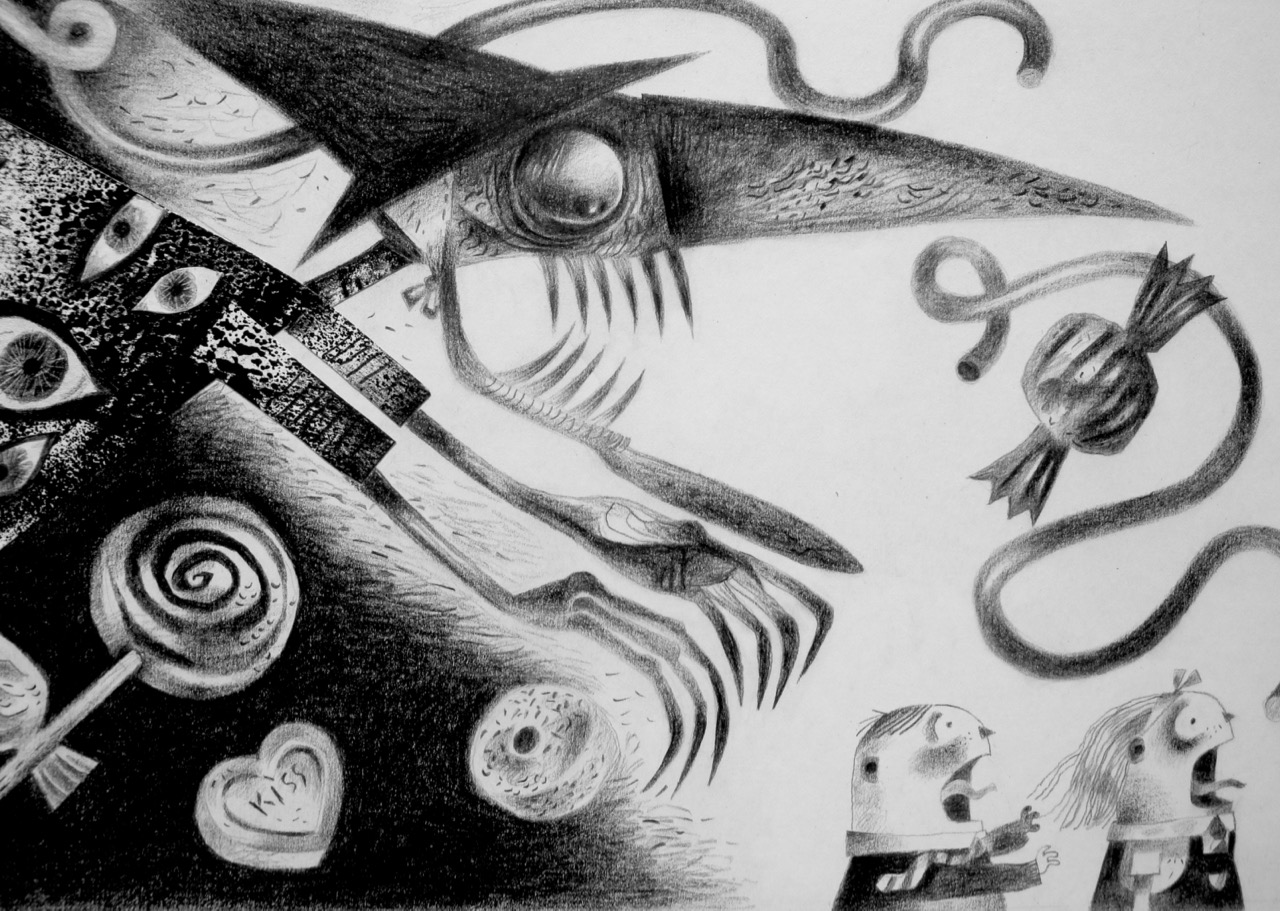

Morgan Le Fay. 2017. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

MORGAN LE FAY

Towards the end of the poem Gawain’s aunt Morgan Le Fay is revealed as the architect of his misfortune. It was she who transformed Bertilak into the Green Knight and sent him to Camelot to test the virtue of her half-brother Arthur’s court. She also hoped to frighten her enemy Guinevere to death.

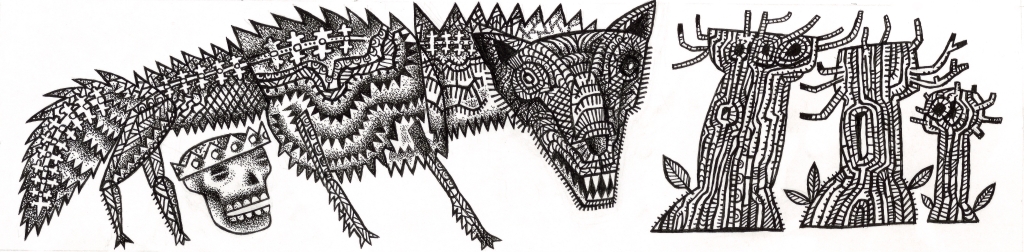

Morgan Le Fay’s role as a villain in Arthurian legend was firmly established by the time the Pearl Poet included her in this story, and more recently she has evolved into something of an anti-hero, a seducer of upstanding young knights and general meddler. Meanwhile critics have argued that she has no real role in this story, and was included to tie Gawain and the Green Knight more closely to the Arthurian cycle, but Clive presents her as an essential player: dark goddess of the timeless wild. She is winged like a bat and crowned like a queen, and rides (side-saddle) a nightmare beast.

In a long and productive career Clive has given us numerous monsters, but this is scarier than most with its shark’s teeth, spiked tail and empty eye sockets. Its gaping mouth might remind us of the Green Knight’s terrified horse, only this creature is a source of terror. It is, perhaps, terror itself. Beneath the wonderful poetry of Gawain and the Green Knight lies the simple story of a young man who discovers that he is human, and afraid.

…

The Stain of Sin. 2018. Screenprint. Edition of 75. 55 x 55 cms

THE STAIN OF SIN

This marvellously rich and varied set of prints finishes, fittingly, with a vivid portrait of Gawain himself, a portrait that shows him forever changed by his experiences. How he has evolved through the story, and through these fourteen prints! First seen as a keen but rather anonymous young knight riding at King Arthur’s side, he then took up the axe to strike the Green Knight and became an individual.

A year later, as he put on armour in preparation for his quest, we saw for the first time the humanity in his face. We have observed him battling monsters and riding proudly on his prancing steed. We have seen him naked and vulnerable, but arrogant too in his youth and beauty. Then horrified, dismayed at his own weakness. Today we might call this ancient tale a coming-of-age story. An untried young man is tested and in the process achieves maturity and self-knowledge.

According to the text of the poem, Gawain is welcomed home as a hero. He confesses all, is forgiven, and Arthur orders the other knights to adopt the green girdle as their badge. Like Bertilak, the king is far more impressed by Gawain’s good qualities than distressed by his flaws. Not so the man himself. He has seen what lies beyond the walls of Camelot. He has known the terror of the timeless wild and his own weakness in the face of death. Indeed, the timeless wild has marked him. First his armour, now his skin.

…

About the Author

James Russell is an independent art historian and curator with a particular interest in 20th century British art and design. His exhibitions include ‘Edward Bawden’ (Dulwich Picture Gallery 2018), ‘Lover, Teacher, Muse… or Rival? Couples in Modern British Art’ (RWA Bristol 2018), ‘Century’ (Jerwood Hastings 2016), ‘Ravilious’ (Dulwich Picture Gallery 2015) and ‘Peggy Angus: Designer, Teacher, Painter’ (Towner 2014, co-curator with Sara Cooper).

When not curating exhibitions, he writes and lectures about 20th century British art, particularly mid-century landscape painting and design. His four-volume series ‘Ravilious in Pictures’ (Mainstone Press) celebrates the life and work of English designer, printmaker and watercolourist Eric Ravilious (1903-42), exploring the stories and characters concealed behind his mesmerizing paintings.

He has also written books on Edward Bawden, Paul Nash, Peggy Angus and Edward Seago, always endeavouring to write in plain English and to explore the artists’ lives as much as their work.

About Penfold Press

The Penfold Press was opened in 2005 by Daniel Bugg as a print studio where artists are able collaborate with a printmaker in order to explore the creative possibilities of a number of printmaking techniques. Working with an exciting group of artists who share an interest in popular art, the Penfold Press has gone on to publish editions of prints by Mark Hearld, Emily Sutton, Ed Kluz, Jonny Hannah, Michael Kirkman, Angela Harding and Clive Hicks-Jenkins.

>>><<<

SaveSave

SaveSave

Gawain has fulfilled the oath made a year ago in Camelot. He’s knelt before the Green Knight and submitted to his axe, but has escaped with nothing worse than a parting of the flesh at the back of his neck.

Gawain has fulfilled the oath made a year ago in Camelot. He’s knelt before the Green Knight and submitted to his axe, but has escaped with nothing worse than a parting of the flesh at the back of his neck.