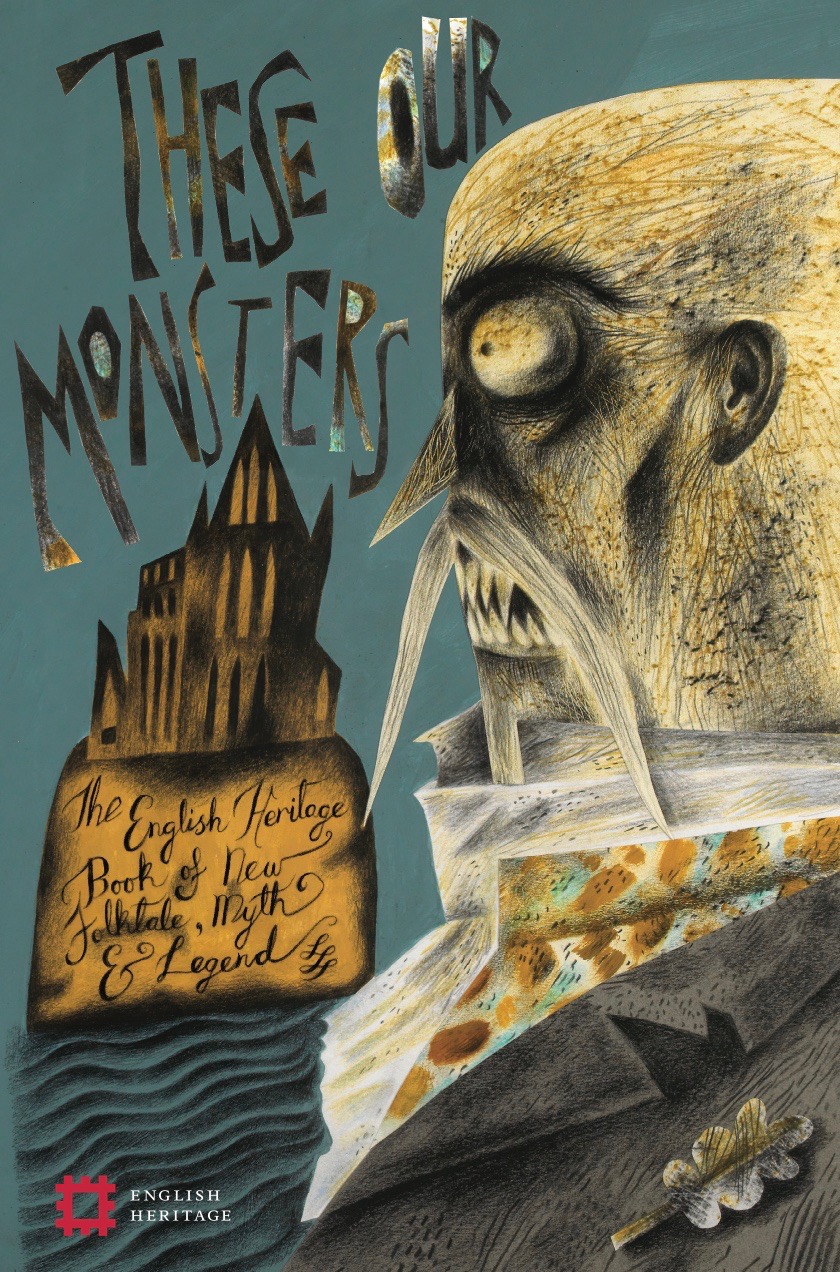

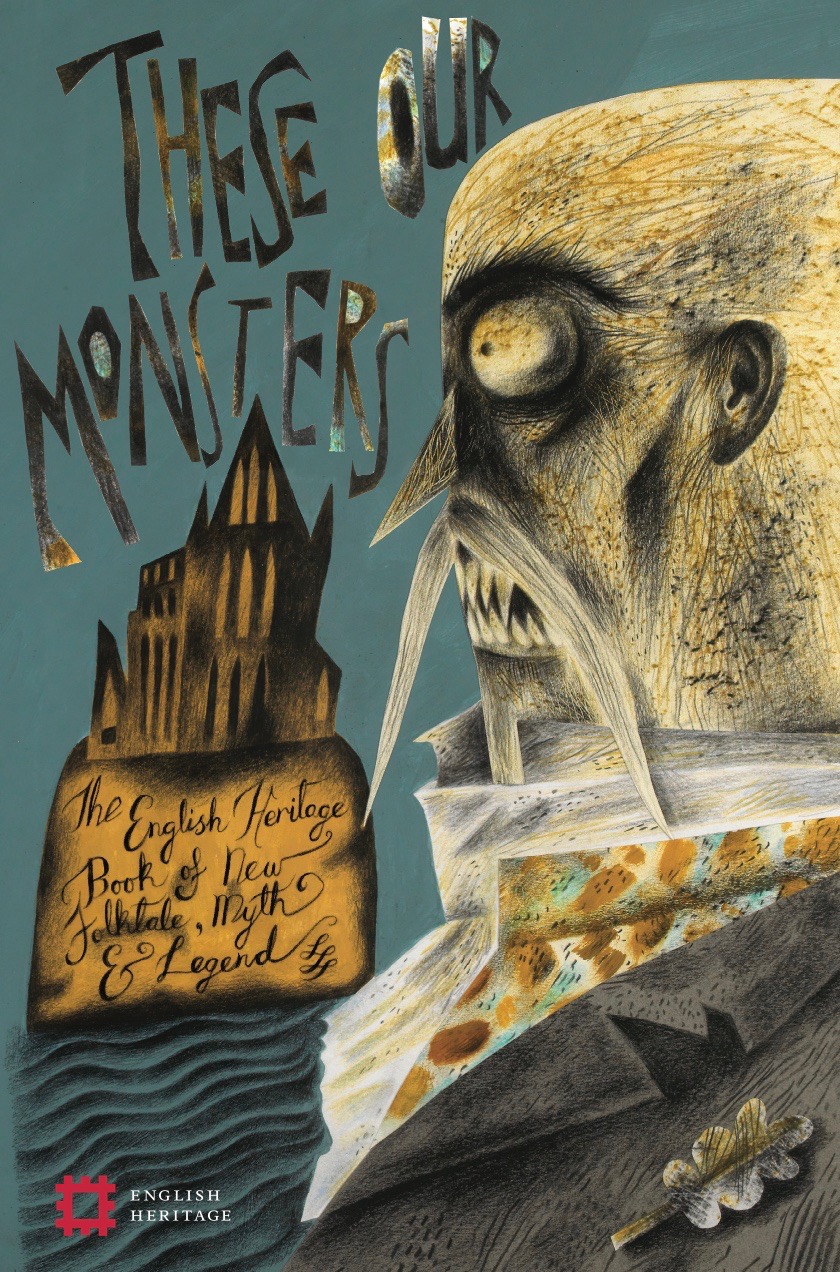

Writer Ed Carey and I have become fast friends since being put in contact with each other by Katherine Davey, editor of the These Our Monsters anthology of short stories for English Heritage.

By way of preparing to make an illustration to accompany Ed’s contribution to These Our Monsters, I also acquired a copy of his novel of the French Revolution, Little, which I read at a headlong pitch and overnight became his biggest fan.

In some ways the friendship is unlikely. Ed self-illustrates his published works and so his contact with other illustrators is limited. However he so liked the drawing accompanying his English Heritage story that he wrote asking whether he might have it, and so we arranged an exchange: he has my framed drawing of a goblin child above his desk, while I have his drawing of a maquette/puppet made for Little.

Below: my drawing for Ed’s story that loaned its title to the These Our Monsters anthology.

Below: Ed built this life-sized maquette of a woman as preparation for his novel, Little. His original drawing of it that appears in the book, was the exchange made for my drawing of his goblin child.

We met for the first time a few weeks ago at an event celebrating These Our Monsters at Hatchards, Piccadilly, and in order to extend our conversation without the distraction of a crowd, again the following morning, for coffee in Bloomsbury, just before he returned to the US and I to Wales.

Dan Bugg suggested that an eavesdropped conversation between me and Ed might offer interesting insights about our processes of producing new work. The projects we talk about are my in-progress print, The Tiger’s Bride, and Ed’s forthcoming book, The Swallowed Man.

…

Ed: Hello, Clive in Wales!

Clive: Hello Ed in Texas!

Ed: Clive, I’ve known and loved your work for years and over the last few months it’s been an absolute privilege getting to know you and even, last week, finally meeting you. What a joy to sit with you and talk about the Lewis chessmen for example.

Clive: Ed, I thoroughly enjoyed our couple of hours in a tiny coffee shop off Gt Russell Street last week. Even though some of the current events we were discussing are horrifying and daunting, we told stories and made each other laugh a lot. One of the great pleasures of illustrating These Our Monsters for English Heritage has been the several good friends made in the process: you, Alison MacLeod and the editor Katherine Davey. I arrived fresh to your writing with the project, but as I’d simultaneously set myself to reading your mesmerising novel of the French Revolution, Little, my responses to your English Heritage short story were being deepened by the wider sense of your creativity.

Ed: You inspire my work and make me think in new ways – to communicate directly is such a wonderful thing for me. And so here we are separated by a pandemic and yet, thankfully, still able to communicate.

Clive: That’s a generous comment. Thank you. The admiration is mutual. The neccessity – or so I find it to be – of a solitary life for a writer or artist, is undoubtedly isolating. (And you, Ed, are both!) We hole ourselves up like hibernating bears because we need clarity and silence to function. However I find the immediacy and creative buzz of being able to bat ideas across great distances with friends and colleagues undergoing the same processes, and in an instant, to be a great joy and solace to what can otherwise be dauntingly lonely. Whether as rich as a prolonged joint creative endeavour, or a humorous two-liner to kick-start the morning before bending to the day’s endeavours, as a man who lives at the-well-at-world’s-end, the swift correspondences of e-mail and messaging have been life-changing for me. The entire process of making fourteen Gawain prints with Dan at Penfold Press was carried out through the medium of daily messaging and the exchange of photos made on our smartphones. I could fire images to Dan of a drawn image on a sheet of lithography film and within minutes be correcting it according to his suggestions. It was almost as though we were in the same studio space. You and I have been showing our individual work projects to each other in e-mails, confident of safely sharing our efforts and misgivings with a creative ‘other’ who understands. It works wonderfully.

Ed: I’m wondering, to start with, what would you say makes a project a Clive Hicks-Jenkins project and what doesn’t? What are you looking for?

Clive: Narrative. Whether obvious or not, whether culled from a source or invented, narrative is always what draws me in. I am an inveterate story teller, and that’s always been my foundation, certainly as an artist but even before that, as a choreographer and director.

Ed: And, specifically, did The Tiger’s Bride come to you or you to it. How did this all start off?

Clive: It started with my life-long love of Staffordshire. The strangeness of it appeals to me. It’s a uniquely of-these-islands combination of folk-art/fairy-tale/dream-world weirdness that always satisfies/disturbs me. The sheep and dogs the size of ponies in comparison to the human figures accompanying them. The theatrical fancy-dress that makes it seem that the handsome men and pretty women are on a stage. The flowers and the often cloying sentimentality, the cottages and castles, the follies and exotic beasts, the bright colours on shining white and the sense of sort-of-familiar yet elusive storytelling being played out on a mantelpiece. Every time I see a doll-like child perched on a monster-sized spaniel or pug, I think about the dog with ‘eyes the size of mill-stones’ in The Tinderbox. Then there are the Staffordshire ‘murder cottages’ and the penny-dreadful tendency to celebrate awful events, most notoriously the escaped tiger with a limp baby dangling from its jaws striding over the prone body of the mother from whose arms the child has been torn. My first print with Penfold took inspiration from the Staffordshire version of Tipu’s Tiger, in which a beast mouths at a slain man in a uniform. The child-like brightness coupled with horror is unlikely and yet compelling.

…

…

The Staffordshire group titled The Death of the Lion Queen had long been catching my eye, and finally I took the moment to begin researching the story on which it was based. I couldn’t shake it. It lingered, took root and I was away.

…

…

I like a long-term project. Gawain had been a nearly three year project. It wasn’t what I worked solely on, except during the last six months when Dan and I had to row like galley-slaves to get it to the finishing line in time to meet the Faber & Faber deadlines and the commitment to the Martin Tinney Gallery for the ‘completion’ exhibition. One of the pleasures of a dip-in&dip-out project is that it has the convenience of being easily set aside and yet ready to return to at the drop of a hat. It’s always simmering on the back-ring of the hob, never unappetisingly stone cold. All my projects tend to be worked on for long periods, and there are always several or even many on the go at any given moment. In the aftermath of Gawain I’d been compiling ideas for a print project that would combine several of my interests: vintage and folk art toys, Staffordshire figure groups, historic circus/fairground traditions and my fascination for toy-like buildings, whether Staffordshire follies and cottages, wooden building-blocks, doll’s houses or the foil and tinsel souvenir cathedrals produced in the city of Krakow. Somehow all this began to tie together with the notion of unspecified fairy stories, and New Folktales was born. The Tiger’s Bride is my riff on Beauty and the Beast, though I didn’t want that title anywhere near it. Angela Carter provided the solution. Here’s a piece I posted at Insta about the event underlying the Staffordshire group titled The Death of the Lion Queen, which was my starting point for The Tiger’s Bride.

…

“This image draws on the tragedy of Ellen Bright, AKA The Lion Queen, who in 1850 at Wombwell’s Menagerie entered a cage of big cats for the entertainment of a paying audience expecting to be thrilled by the spectacle of a girl commanding ferocious beasts. At just seventeen years old, Ellen was celebrated though relatively inexperienced, and it may be that on the day her ambition outstripped her judgement, because a reliable eyewitness in the audience afterward observed that from the moment she entered the cage the tiger displayed unmistakeable aggression toward her. At a sting to its face from her whip, the animal lay down. Ellen turned her attention to the lions, but then – perhaps for good measure, or perhaps because at that moment she intuited the dangerous state of the beast – turned back and stung it for a second time with her whip in its face. The tiger rose, reared and lunged at her head, seizing her in its jaws and bringing her down.

Ellen sustained catastrophic injuries to her lower jaw and throat, and according to a doctor who was in the audience and attended her after the attack, she died within minutes without recovering consciousness. So horrified were the public by the tragedy that thereafter the law was changed, forbidding women to enter cages with big cats for the purposes of entertainment.”

…

Below: contemporary illustration reporting the death of Ellen Bright at Wombwell’s Menagerie:

…

The Staffordshire pottery workshops quickly produced, or perhaps adapted, an existing ‘Lion Queen’ group in order to commemorate the event, adding the wording ‘Death of the Lion Queen’ to capitalise on the public interest. (Ellen was not the first Lion Queen, as there had been several who’d gone by that title before her.) I’ve referenced elements from several Staffordshire groups of a girl performing with big cats, but have gone my own way in expressing the subject.

…

Below: early study and final layout-drawing for the print.

…

Ellen’s story is tragic, and not just because of how she died, but because large cats in 19th century menageries must have been driven insane by their ill-treatments and confinements. This piece is not about that – though the idea is running beneath it – but is an exploration of the fairytale theme of the beast/groom.

…

In the same way you’ve taken the novel of Pinocchio and used a lightly-touched-upon back story in it as the foundation of your new novel The Swallowed Man.

Do you find that using an existing theme/story as the bedrock for a new telling is a good method of creativity for you? Which came first for you here, Jonah and the whale or Pinocchio’s dad/maker? (I feel Pinocchio might profitably be examined in comparison with other ‘man/woman-making’ stories/myths, including Frankenstein and Galatea/Pygmalion.)

Clive

Ty Isaf

20/03/20

Gawain has fulfilled the oath made a year ago in Camelot. He’s knelt before the Green Knight and submitted to his axe, but has escaped with nothing worse than a parting of the flesh at the back of his neck.

Gawain has fulfilled the oath made a year ago in Camelot. He’s knelt before the Green Knight and submitted to his axe, but has escaped with nothing worse than a parting of the flesh at the back of his neck.