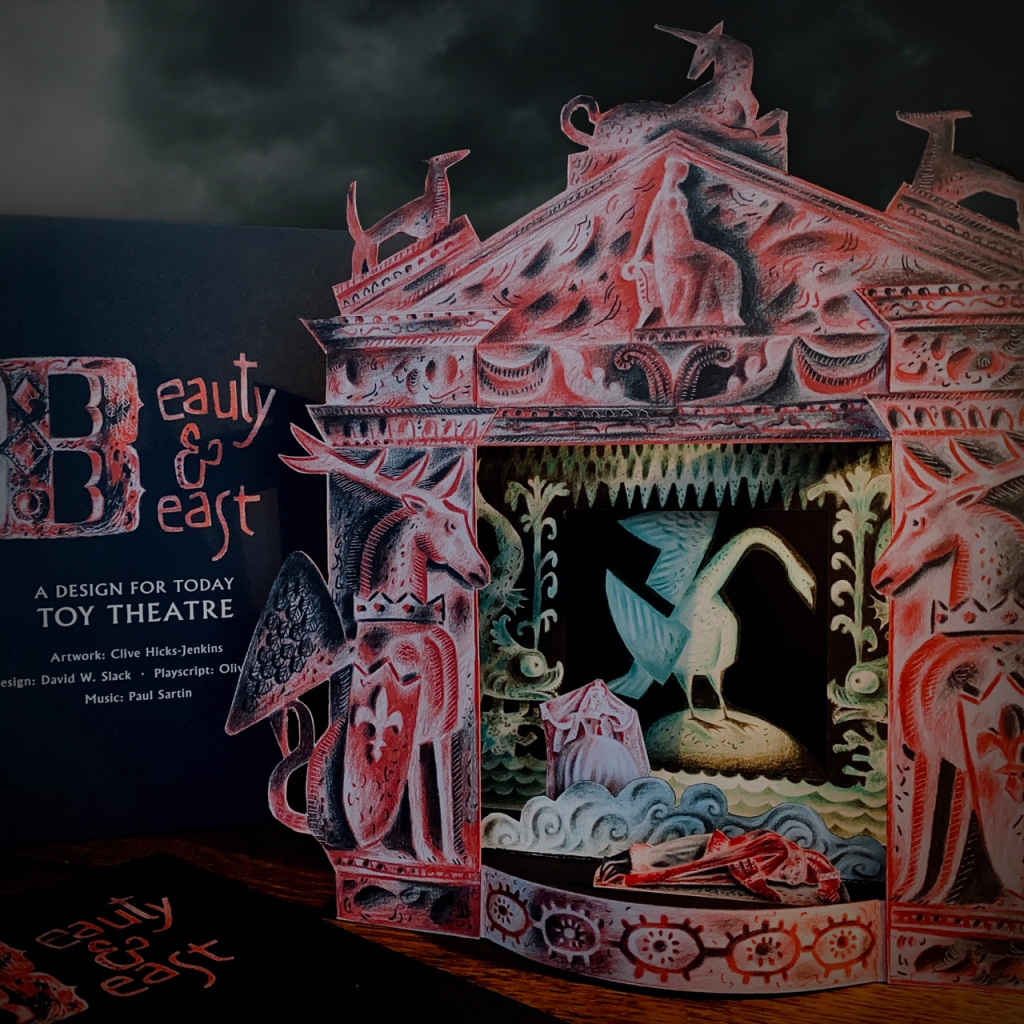

On June 27th Folio Society will be launching their ‘special edition’ of Beowulf, translated by Seamus Heaney and illustrated by me. Heralding this are two animated films to celebrate the event, produced by my regular collaborator of the past few years, David W. Slack. David is a painter in his own right, and it’s his breadth of knowledge and practice as an artist which strongly underpins what we make together. We first collaborated when I asked him to construct preliminary models for the Beauty & Beast Toy Theatre Kit I was preparing for publisher Joe Pearson at Design for Today. In this first of two recent ‘conversations’, David and I track how he went from model designer on Beauty & Beast to being appointed Animation Producer on Beowulf.

Clive: David, I first came across images of yours at Insta when you were ‘enhancing’ your copy of the Hansel & Gretel Toy Theatre I’d designed for Benjamin Pollock’s Toyshop. What first struck me was how good a model-maker you were, followed swiftly by how improved the model was by the curved stage-front you were adding to it. “Damn it!”, was my initial response. “I wish I’d thought of that.”

Above: David’s ‘improved’ Hansel & Gretel Toy Theatre, with the footlights and curved stage-front he added.

David: That model was really lovely. When it arrived I was amazed at how few sheets you’d managed to condense the entire story into, yet when cut and assembled it became a very layered and complex model. You sent me the additional scan of the stage floor so that I could print the floorboards I needed for my planned stage extension.

Clive: For the record you’re a better model-maker than I am, and I remain envious of your framed model of the adapted Hansel & Gretel Toy Theatre complete with lights and curved apron. Overworked as I was by this point, the idea of inviting you to collaborate on the Beauty & Beast Toy Theatre was already churning away in my head keeping me awake at nights.

David: I’d seen an Insta post of a beautiful architectural doorway you’d made for Beauty & Beast flanked by sinister white-eyed caryatids. Having contacted you to ask how you’d feel about my interpreting the idea into a painted wardrobe, you were extremely encouraging.

Below: preliminary work on an illustration of a garden door in Beast’s realm.

When I ventured further and wrote that a toy theatre might be fun, you admitted you were planning one, had a preliminary dummy on your desk at that very moment and were wondering whether I might help with it. After that it was just a case of me trying to jump onto the already speeding train!

Your work on the book of Beauty & Beast with writer Olivia McCannon was already well underway, and although that collaboration was quite separate to the toy theatre, the two projects were clearly intended to be viewed as a pair. From the start your advice to me was to “do less”, and it was much needed as my first response was to turn the model into the toy theatre equivalent of a big old Busby Berkeley number in a Hollywood musical. Fortunately, better understanding that a lighter touch benefits toy theatre, you stayed my hand. More sketches went back and forth to get us to the same starting point, and thereafter everything was much clearer. I outlined my understanding of my role as the facilitating designer who’d translate your evolving illustrations for the book into a working toy theatre model.

Clive: And that was a good starting point for both of us, though in fact your role quickly became much more than that of model designer. With sections of Olivia’s text for Beauty & Beast arriving daily I was up to my eyes in keeping apace with my illustration schedule, so it was a relief that you were able to efficiently keep me up to speed with what you needed for the model and when. You’d effectively become the project manager.

David: Once bedded in I began to lobby for an increase to the six construction sheets you’d advised were the maximum we could afford for the model. I hope I wasn’t too pushy.

Clive: I saw it more as a case of your enthusiasm for what we were making. However while excited by what was emerging from your desk, I was growing slightly anxious about the implications for the budget. It was time to explain to Joe the publisher that I’d gained a collaborator, and to sound him out regarding expanding the project from six to ten sheets. By now you were producing prototypes like a man on a mission, and with the tangible evidence of what we were achieving, Joe agreed to the new proposal.

David: SO many prototypes, yes. How my printer didn’t explode I will never know. I was desperate to get the maximum-sized model into the smallest space, so there was a lot of jiggery pokery.

That in the end we fitted so many scene changes alongside puppets and props onto just ten sheets still amazes me, because the toy theatre alone took four. More than anything else I wanted to include the scene of the disembodied candelabra-bearing arms in the entrance to the castle, and I was at the point of offering to personally underwrite any added expense for them when you came back with the news that Joe had agreed to the extra sheets. We were up and away.

Clive: It was quite a roller-coaster we were all on. This was new territory in nearly every respect. The project was complex and we were all aware of how it needed to fit with the main book, while also being separate and stand-alone. Already it was apparent there needed to be considerable adaptation from what I was creating for the book, to what would work for a toy theatre.

Always there’s the line to be walked between being prudent with the budget, yet open to where a bit of extra funding will give real added value. Joe kept everything under close scrutiny as we progressed, and his was the suggestion to present the ten sheets in a folder with pockets, instead of being bound into a book. The script and instructions could then be produced as a small pamphlet, which in the end worked beautifully and saved costs.

David: I was amazed at how quickly everything progressed. It was only later I realised what a frenzy you were in trying to keep up with me, all while I was feeling the need to go faster to keep up with you! But we steadied our nerves and in the end the toy theatre was made at an incredible lick, and it looked wonderful.

In the next post we move on to Beowulf and how David took on the role of Animation Producer for the two Folio Society films he was asked to create to promote the new book.