It’s with huge delight that I can reveal, at last, that my current big project is the commission to illustrate a new Beowulf for The Folio Society, in the acclaimed translation by Seamus Heaney. The illustrations must remain shrouded in secrecy until the book is ready for launch, and I won’t be showing work in progress. Suffice to say that I’m already deeply bedded in the project, awakening every morning excited to be in the thick of it and enormously enjoying the many discussions and planning sessions with my wonderful Folio Society art director, Raquel Leis Allion. But this little vignette is all you’re going to see before the book is published, because we’re keeping the images under lock and key.

I’ve greatly enjoyed the notion of ‘the monster’, whether in novels, in film/tv or in folklore and mythology. Aged eight I was sold on the idea of the ‘Gorgon’ from the first moment I read about her, and the Hydra, too, and the three-headed Cerberus, guard-dog of Hades. As a child, when too young to actually see X-rated films, I pored over imported copies of Famous Monsters of Filmland, so I knew all about the Universal Studios monsters – which were vintage even back in the fifties when they were being given lush spreads in the magazine – long before I ever saw the films themselves. I thrilled to the images of Lon Chaney being unmasked in The Phantom of the Opera, of Bela Lugosi curling back his lips in a pasty-faced vampiric leer, and Karloff sitting in Jack Pierce’s makeup chair being transformed into one of the most iconic monsters of cinema history.

I’m not a fan of all ‘horror’ – in extreme form I find it distasteful – but when makers are creative in producing something that nails you to your seat, the ride can be thrilling. I particularly love it when the scary bits are not too in-your-face. One of the greatest strengths of Alien, is that it pre-dated CGI, and so the fully-grown creature is half-shadowed and all the more alarming for it. I think the best scares in Jurassic Park are in the kitchen where a pair of Velociraptors hunt down the children, because most of what you see is staggeringly clever animatronics and puppetry, made even better by masterful editing. When the monster is actually there, in close contact with the actors, and not just a man in green wielding a ball-on-a-stick to cue their eye-lines for special effects to be added later, there are worlds of difference in the performances.

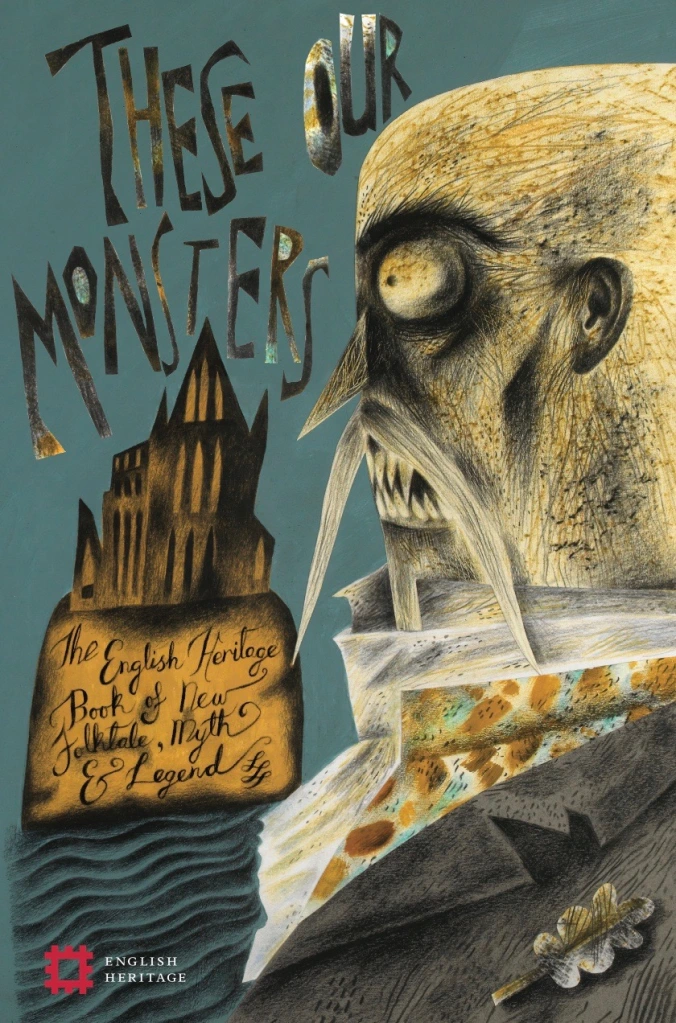

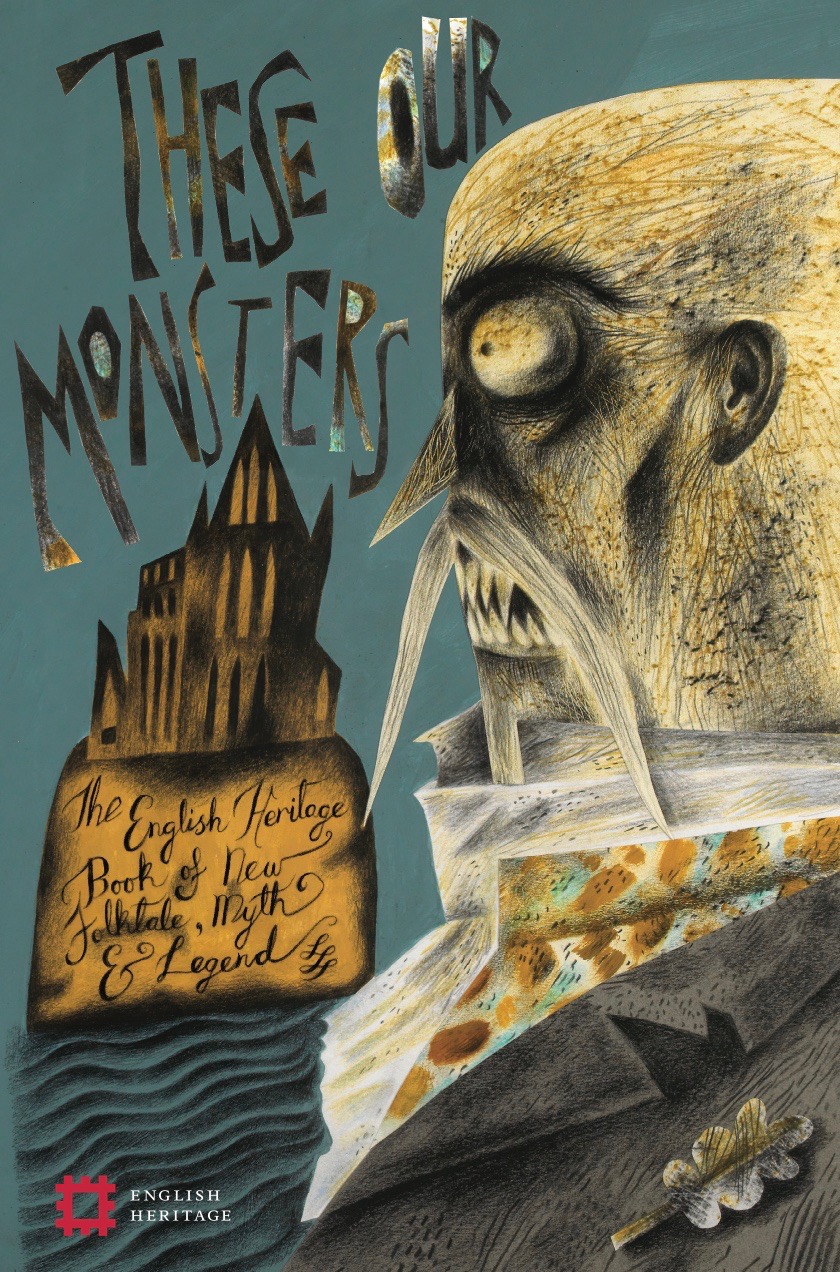

I’ve particularly enjoyed it when I’ve been given illustration opportunities to engage with old-school classic creatures. For the cover of These Our Monsters (2019, English Heritage), I was able to trace back to Bram Stoker’s account of Vlad Dracula, which was quite an eye-opener because the original descriptions are not remotely like any of the character’s film incarnations. (The cover image here is for The Dark Thread by Graeme Macrae Burnet, who sets his troubling and elegiac short story in Whitby at a time when the mentally fragile Stoker has returned to confront his own creation.)

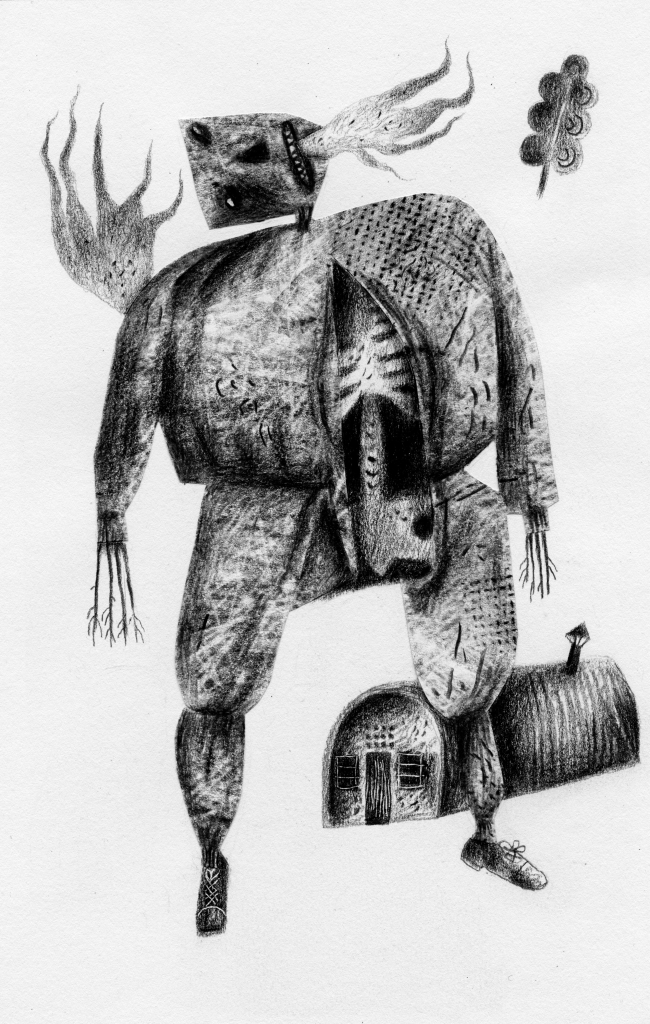

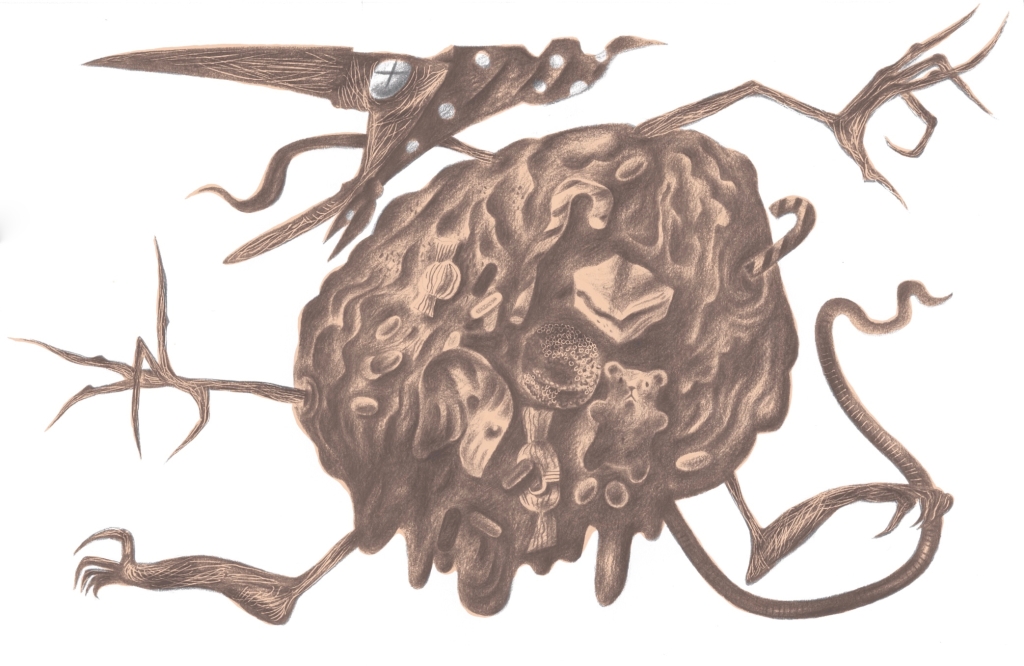

There were entirely new monsters in the book, too, and I loved creating what Sarah Hall only suggests in The Hand Under the Stone, which is about as close as I’ve ever come to making a monster inhabiting a similar ‘between-worlds’ plane of existence to those found in the ghost stories of M. R. James which I love so much.

I’ve made several varieties of Witch for two quite different books on the theme of Hansel & Gretel, for a stage production in which she was presented via shadow-puppetry, and for a toy theatre for Benjamin Pollock’s Toyshop.

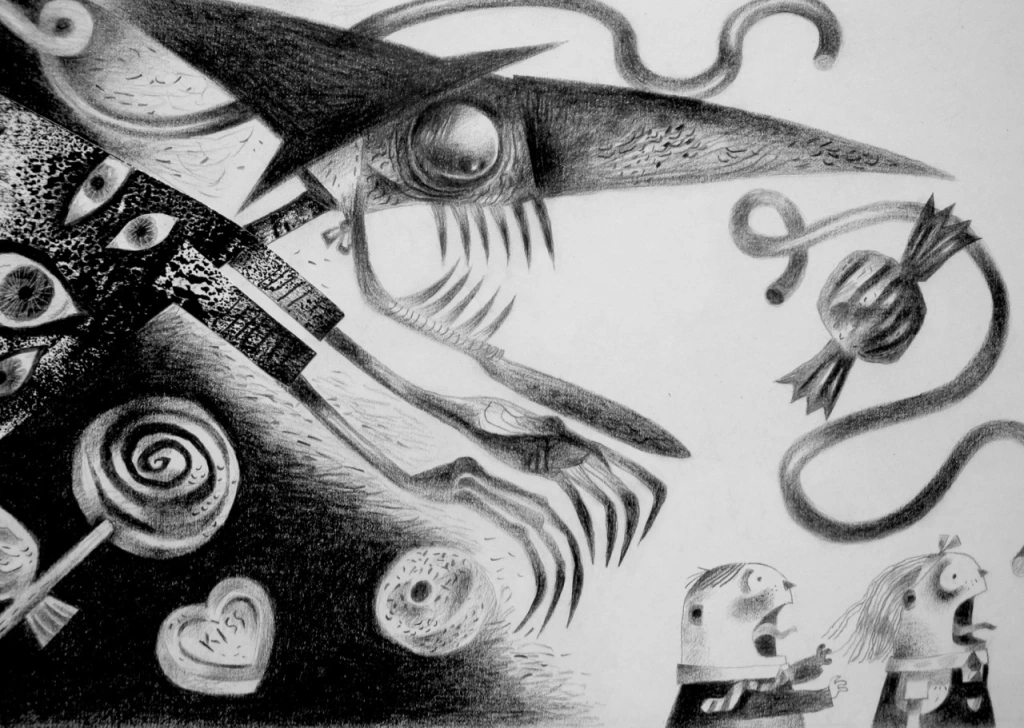

My first Hansel & Gretel book was a more or less textless picture-book for St Jude’s in which there was a Witch scary enough to require a warning for more sensitive readers. I made her glaucous-eyed and short-sighted – as witches traditionally were in some folk and fairy-tales, the Grimm Brothers telling of Hansel & Gretel included – but I dressed her in a garment embroidered with eyes to send out a different kind of message. (I stole the idea from a portrait of the first Queen Elizabeth in a gown embroidered with eyes and ears, as a coded message to her subjects – and more particularly her enemies – that the monarch saw all and heard all!)

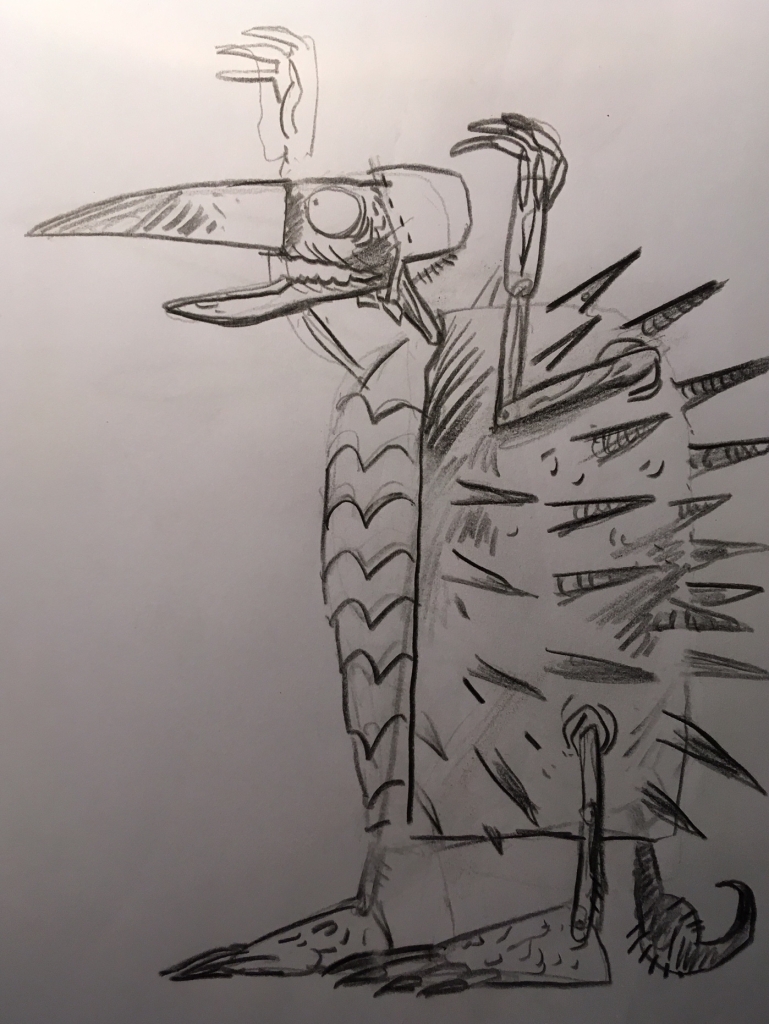

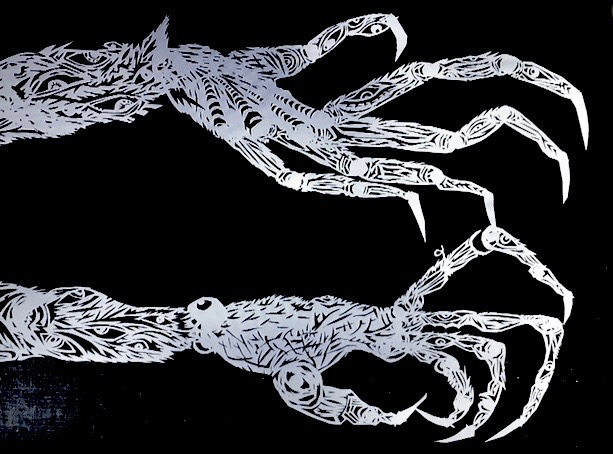

For the Simon Armitage version of the tale, Hansel & Gretel, a Nightmare in Eight Scenes, I collaborated with paper-cut artist Peter Lloyd, providing him with rough drawings that he then transferred into elaborate stop-motion shadow-puppets. To begin with Hansel and Gretel saw only a crone in a bonnet and cloak, but when the cloak came off, the full horror of a spiny crab-like carapace was revealed, reverse-joint legs – like a bird – and a tail with a stinger that snaked into view and coiled and thrashed about.

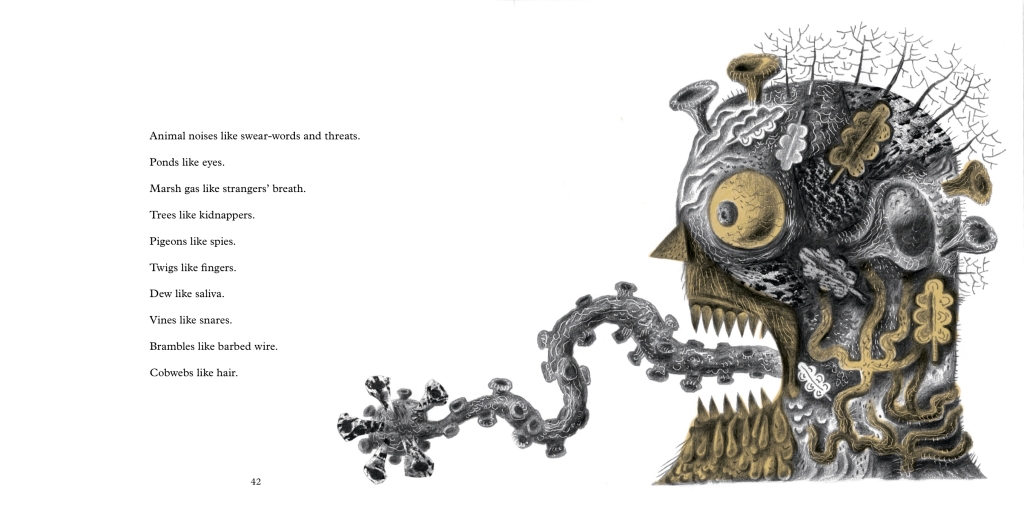

When Simon Armitage’s libretto for the stage production was published in 2019 as an illustrated book by Design for Today, I made a monstrous Witch – seen below as she’s turned into a gobstopper when Gretel pushes her into a cauldron of sweets boiled down into molten sugar – and a monstrous personification of the haunted forest, too, wonderfully described by the poet in a text that’s an illustrator’s dream.

Beowulf is jam-packed with the eponymous hero’s encounters with monsters of many varieties. There’s a deep-sea-creature that drags him to watery depths, a dragon he slays – though he becomes fatally wounded in the process – and that arch-monster of literature and father of all horrors that came after him, Grendel, who is of a sufficient size to stuff thirty human corpses into a bag and make off with them. Beowulf tears off Grendel’s arm as a trophy, and the fatally wounded monster slinks away to die ‘off-stage’. We then discover there’s worse waiting in the wings, for Grendel has a mother, and she’s as wrathful as a nest of Asian Hornets on the warpath when she sets out to avenge her son’s death. (And you thought the vengeful mother was invented by the makers of the second Alien film. Turns out that she goes back to Anglo-Saxon literature, and before that to even more ancient mythologies and tales.)

So I am thrilled to be making images of these archetypal monsters, and hopefully in ways that will be unexpected and visceral enough to raise a few hairs at the nape of the neck. But in a good way, of course.