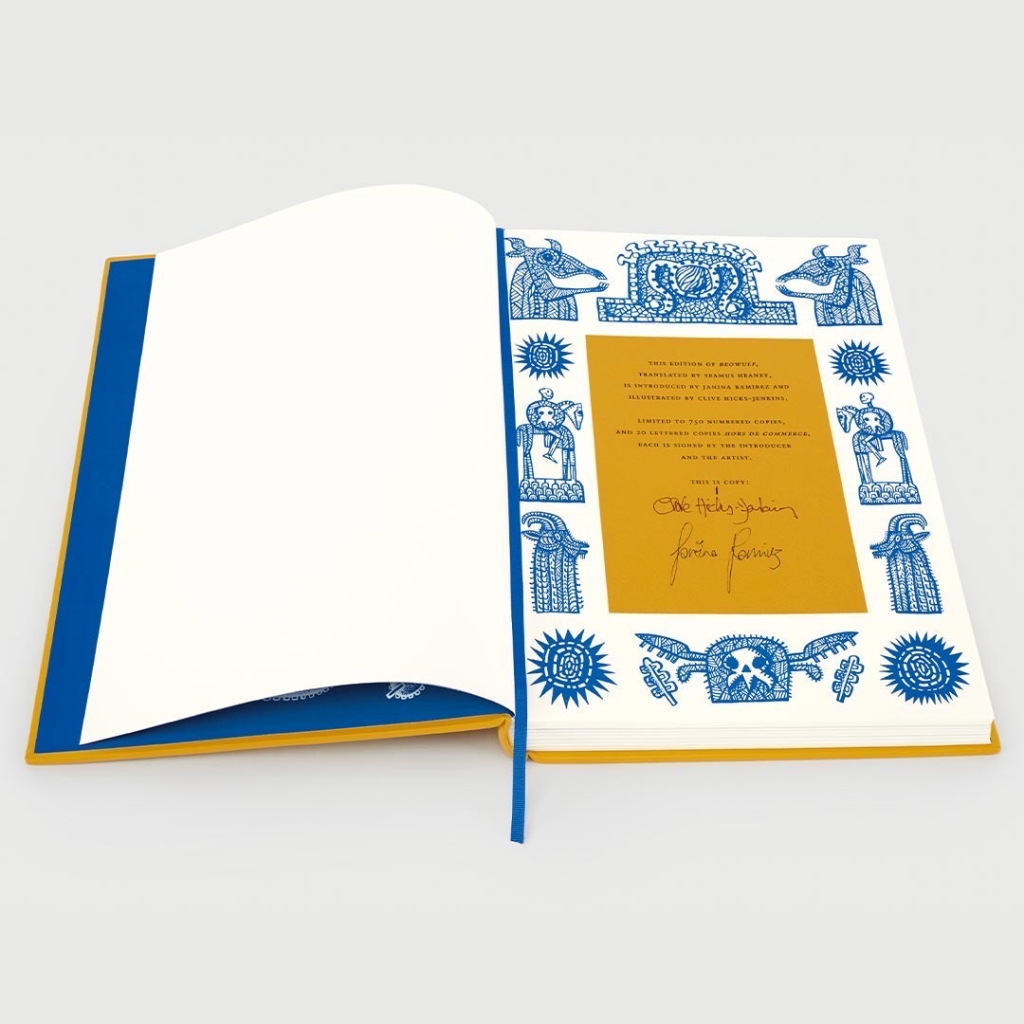

Please Click on the title above to watch the videos embedded in this post.

Above: click to view the book trailer for Beowulf

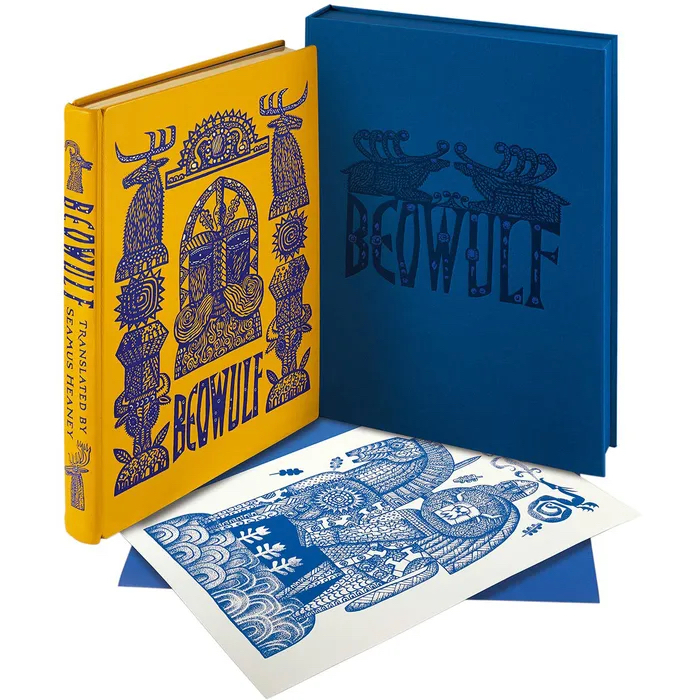

Clive: David, you were undertaking trial digital work for me while I was working on the illustrations for Beowulf. I made them in black ink on white board, but had it in mind to see how they’d look when inverted to white on black. What you produced provided me with inverted images of drawings and digital colourings of them throughout all the earlier stages of the book’s creation. Although the final additions of colour were done at Folio Society, you did all the preliminary ‘tests’ that enabled me to make the decisions ready to brief the Folio team.

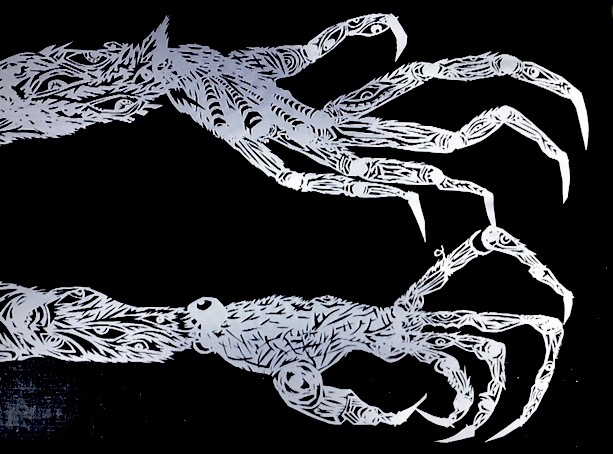

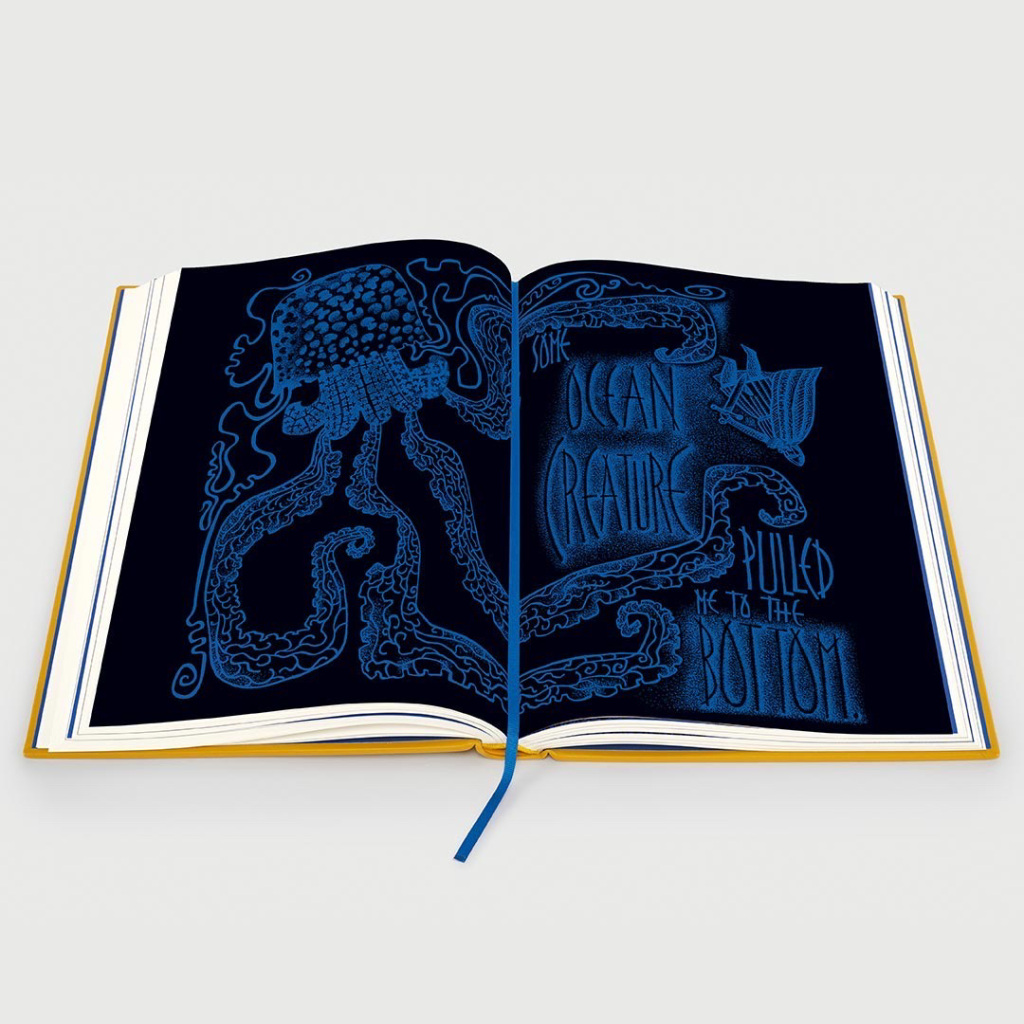

Above: detail of illustration from the book after image inversion and digital colouring by Folio Society.

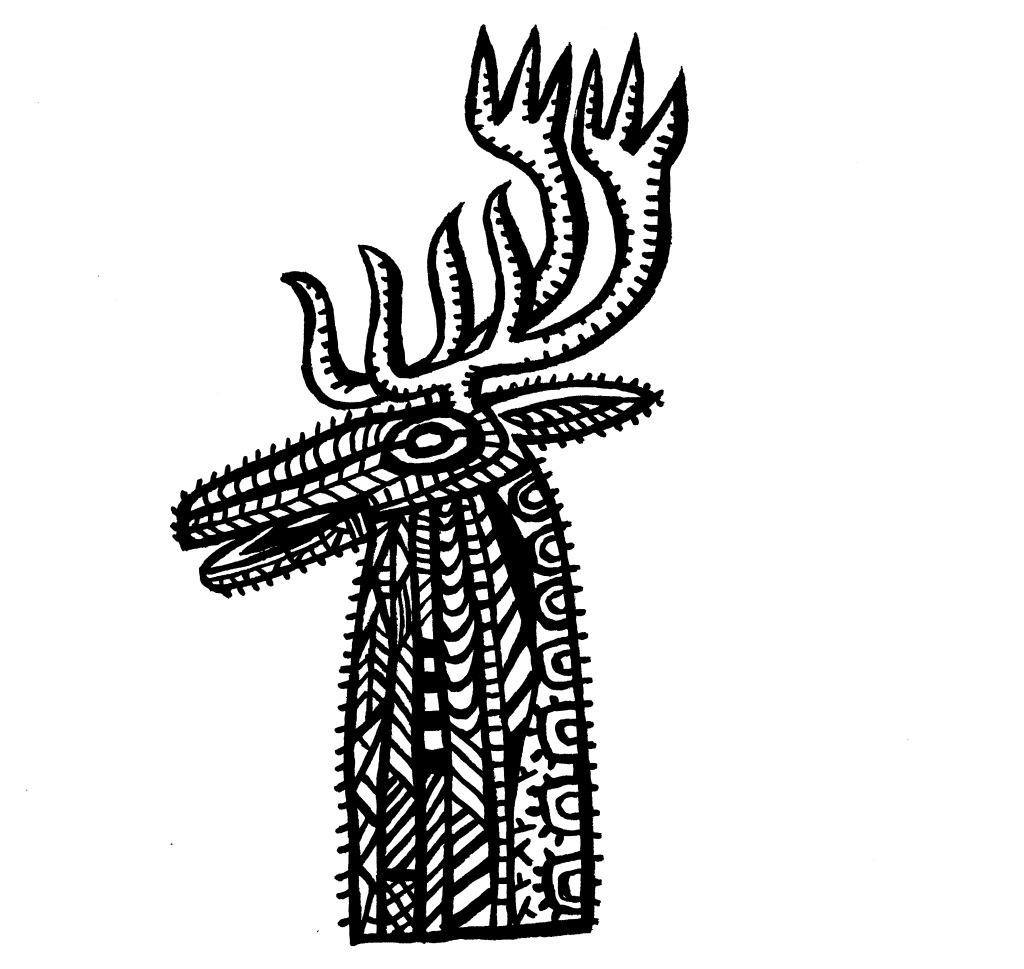

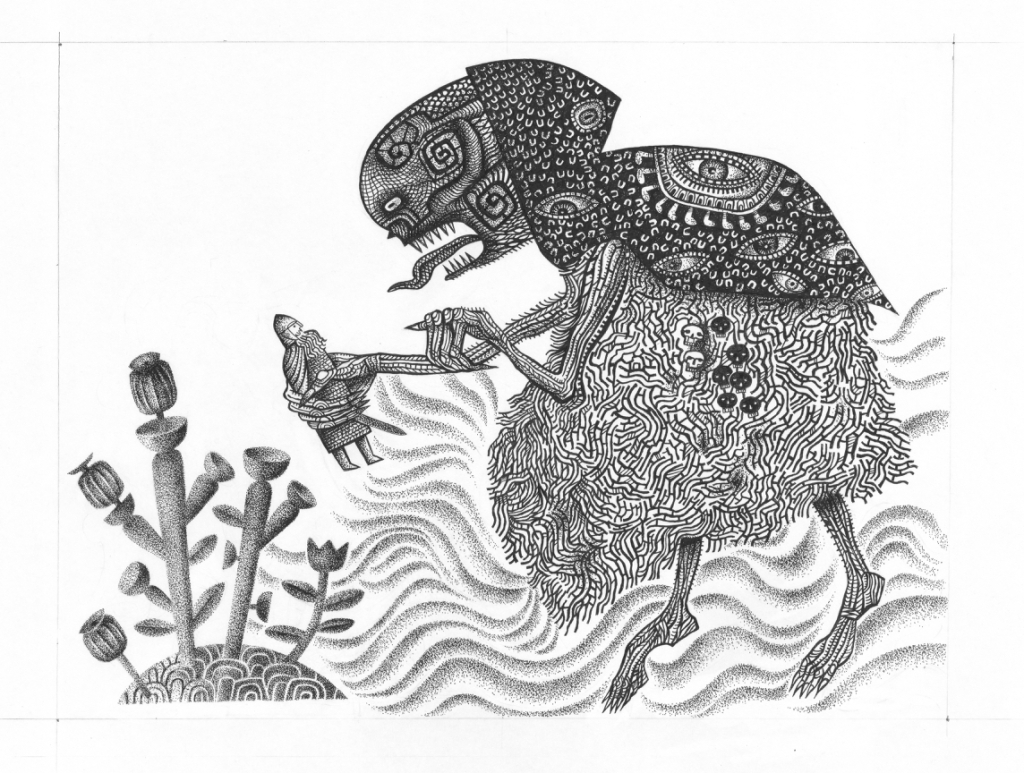

Below: original ink artwork on mountboard with pencil trim guide, before inversion and colouring.

David: Oh it was such a joy to have a private viewing of your Beowulf drawings, and because I was messing around with them digitally, I could easily produce many different versions. It was fascinating wasn’t it, that some worked instantly as inverted images, while others were more powerful as you’d drawn them?

Above: finished ink drawings piling up on the artist’s desk.

Clive: In the end we included some drawings as made and some inverted. The combination worked well.

David: I made some red versions which were just OK, but I remember layering a deep spot-lit blue-green with the image for the first time, and it pulsed and sang immediately.

Below: trial colour images of inversions made by David.

But I think you had committed to the blue at that point, and the intensely saturated blue-on-black and black-on-blue that their production manager achieved in print for your full-bleed double-page illustrations, is way beyond anything I’ve ever seen in print. I’ve done a lot of printmaking through the years, but how they achieved that glowing deepest blue is beyond me. It pulses with some sort of other life and is just unforgettable. I know that you were blown away by the book when you saw it.

Clive: I couldn’t stop shaking when I received and opened my copy. I was anxious because I knew by this point the edition was printed, bound and boxed, and there could be no turning back. I’d seen many page proofs over the months, but between the last proof seen and the finished book the production manager had worked miracles. I was simply speechless when I saw the the quality of the printing.

Because of your contributions at preliminary stages, and because you knew the illustrations inside out, it was inevitable that at some point we’d start talking about the potential of the images to be animated into life, and that’s exactly what happened.

David: Well of course, what a gift this was! Your drawings for Beowulf were in a paper-cut style, and so ready-made for shadow theatre puppetry. I’d learned to animate a while back when we’d made an animated film to promote the Design for Today Beauty and Beast Toy Theatre. With that experience under my belt, how difficult could it be to create a three or four second animation as a test run for a potential Beowulf book-trailer? I have to say that it was BLOODY difficult. I’m pretty sure that the learning curve was so steep that at more than one point my neuron’s firing registered on Google Earth. But anyway, this idea of a moment of animation er… well, it snowballed rather didn’t it?

Above: articulated paper maquette made as a compositional aid during the early stages of planning the book.

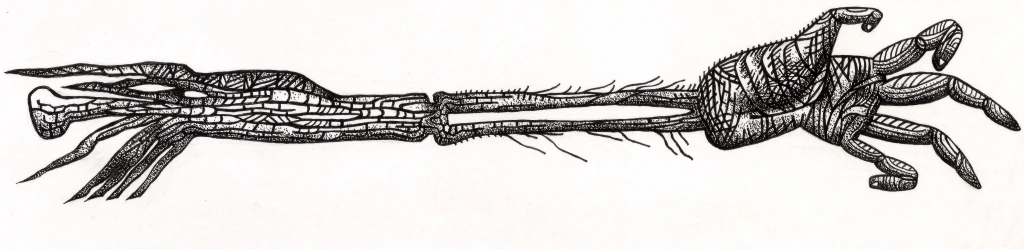

David: Much of your preparatory-stage work for illustration is built upon the idea of the jointed maquette, so animation is a perfect fit. And of course you’ve made many frame animations in the past, for example on your stage productions of Hansel and Gretel and The Soldiers Tale. By now you and I had made many animations together, almost all set within the bounds of a toy theatre. The images of Beowulf were so exciting to imagine unshackled and animated into life. They were perfectly suited to the medium.

Clive: Because we felt some animation sequences could enhance the promotional video Folio would be sure to make to launch the book, I decided to ask them whether they might consider permitting us to submit a couple of trial animation sequences by way of introducing the team to the idea. Luckily they were open to that and you began work almost immediately.

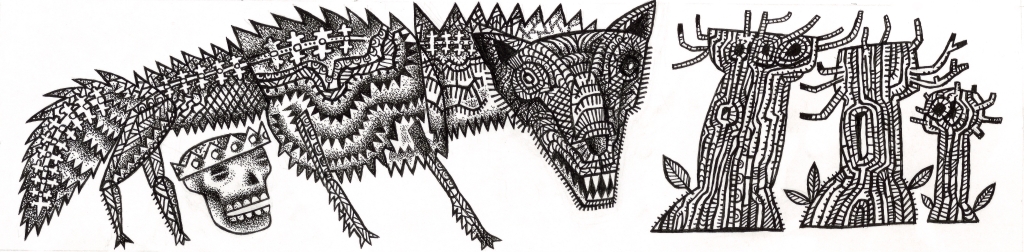

I recall conversations we had about the ‘character’ of the animation, degrading the imagery to make it look almost like ‘found footage’ with that sense of vintage film scratchiness and fluttering. You might have different recollections to me, but among references we discussed there was the idea to animate the dragon almost as if it were some kind of nematode worm being filmed on a slide under a microscope. I think I may have mentioned the title sequence for the film Seven to you, with its sense of flickering unease. And then of course there was our shared passion for Smallfilms and the work of Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin. It’s just not possible to be in a world of Norsemen without having a conversation about Noggin the Nog.

David: Ah yes! The David Fincher/Smallfilms mash up. I loved your suggestion of a squirming dragon as a micro-organism under magnification. It adds an edge of discomfort to see inserts of a different texture, speed and animation style within the piece. I used the same concept in the jerking movements of the wolf and the tentacles whenever they appear.

Above: black original ink drawing and the digital translation to colour in the book.

David: Tonal changes are essential to my mind, especially when the piece is very dark, or heavily stylised. The most incredible imagery in a movie can actually become dull after a while, unless the viewer is shaken out of it – like a little hit of spice. I watched versions of scenes of the Beowulf animation without the degrading filters we talked about. Your drawings moving across the screen were so striking without the added optical effects that I found it tough to dull them down. Nevertheless I added scratchy inclusions of scrabbling colour to make the films glow and dull in turn, and the decision worked wonders in unifying the animations and the sequences of the book itself. One of the things I had to keep reminding myself was that this wasn’t a trailer for a movie, but for a beautiful book. (The Hitchcock in me was forever edging it to a movie trailer.)

Clive: We waited with bated breath once the sample shots had been delivered to the Folio team, but when the responses came they were wholeheartedly enthusiastic. Far from delivering a few short cuts to be edited into a promotional film, we were tasked with producing the whole shebang. After a briefing Zoom with the team at Folio we got working. There were to be 2 x 30 second films, one at a format for viewing on smart-phones, and a second for viewing on laptops and tablets.

David: Oh weren’t they wonderful? They showed such faith in us that I did feel confident about how it would turn out. Working with such carefully considered and rendered drawings I knew the results would be beautiful. Like cooking with the best ingredients. Although the brief was for 30 second films, I overshot and both edits came in at one minute and six seconds. I think just over the minute stands up very well. I would have been pushed to get the pace right in 30 second films.

Clive: I agree. 30 seconds would have been too rushed. As the films stand, each at just over a minute, they fly by when watching them.

As with all our animation projects, once we’d discussed I absented myself to concentrate on sourcing the music. You in the meantime were off like a rocket. I remember your utter confidence that you knew where to go with all this, waiting only on the music to provide the structures to the films. You were not just animator on the project working to my brief. You were now Animation Producer!

David: And a very cocky one at that, due in no small part to the confidence and enthusiasm you demonstrated in allowing me to hack up and rearrange your artworks.

While you researched the music, I got busy anatomising your Beowulf characters to assemble a cache of puppet elements. You always show an astonishing faith in me to infill the drawings when I amputate an arm, head or leg, or need to find fingers or a neck. I in turn feel safe in the knowledge that you’ll always find the perfect piece of music which will make the pace, depth and rhythm of the story appear clearly in my head. This time you found four tracks, one of which though amazing, we both thought a little too disturbing. (Maybe it’ll be right at another time for another film.) I viewed the films hundreds of times when making them, and have watched them many times since completion. I’m confident the two music pieces we settled on had just the right aesthetic, power, drive and primal drama. People report that they watch them repeatedly, and a big part of that is because the music makes them so moreish.

Above: click to view this animated book-trailer for the new Folio Society edition of Seamus Heaney’s translation of Beowulf.

Artist: Clive Hicks-Jenkins

Animation Producer: David W. Slack