In 2019 Olivia Ahmad wrote about Clive Hicks-Jenkins’ explorations of Hansel & Gretel for Varoom magazine.

Clive Hicks-Jenkins’ retellings of classic fairy tale Hansel & Gretel have an edge. Taking in the original tale’s horrific neglect, abuse and murder, Clive has adapted the story into a picture book, toy theatre and original stage production. Olivia Ahmad looks at Clive’s startling manifestations of the familiar story.

“The boy was called Hansel, the girl was called Gretel – hence the title, Hansel & Gretel.” So the narrator opened Clive Hicks-Jenkins’ 2018 staging of his version of the European folk tale, first recorded by the Brothers Grimm in 1812. The performance had the subtitle a nightmare in eight scenes, which undermined any notion that Clive’s combination of animation and puppetry would be a saccharine adaptation of the story of the witch who tempts two lost children into her house made of gingerbread. “It’s a dark and brutal story”, he says, “the mother has been cruel and treacherous, and is dead by the time the children return home, with no explanation of what happened to her. Gretel has killed the witch in the most dreadful manner, which is not just something you can brush aside. There will be psychological scars. So the story is odd and downright nasty and has too often been glossed in endless re-tellings. It was just too good a chance to miss.”

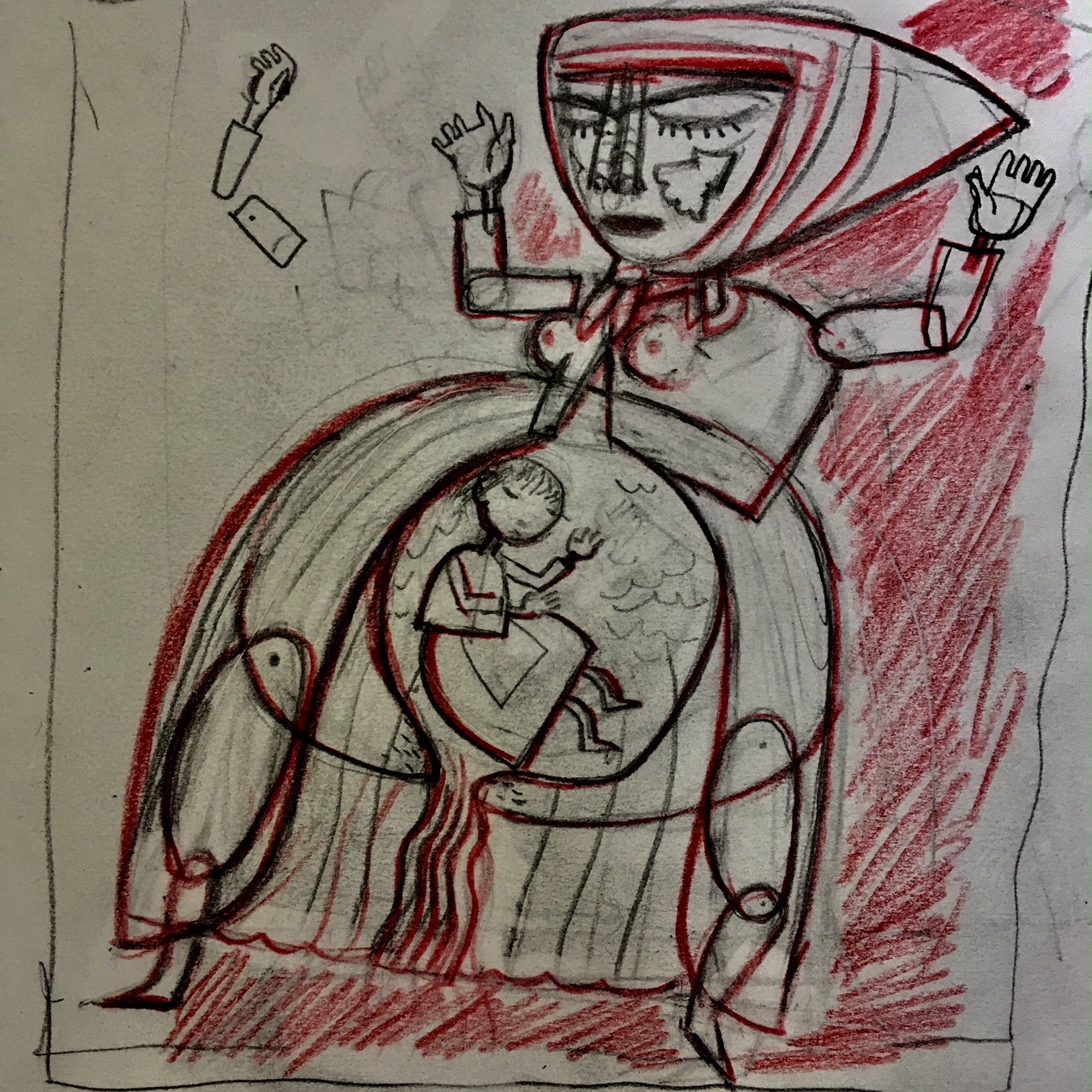

Clive first took up the chance to envision the story for a book in 2012, inspired by a childhood memory. “I had a Toby Twirl annual,” he explains. “There was a story of a witch who captured Toby and imprisoned him. The pictures of her terrified and enthralled me. She stuck like a burr in my imagination and she’s been there ever since. When in an idle moment some years ago I felt the need to be drawing a witch, I chose Hansel & Gretel as the vehicle simply because a witch was central to the plot. I painted the characters onto a set of enamelware plates for a bit of fun, for no other purpose than for use at home. And in so doing, I laid the foundations for the larger project, though I didn’t know it at the time.”

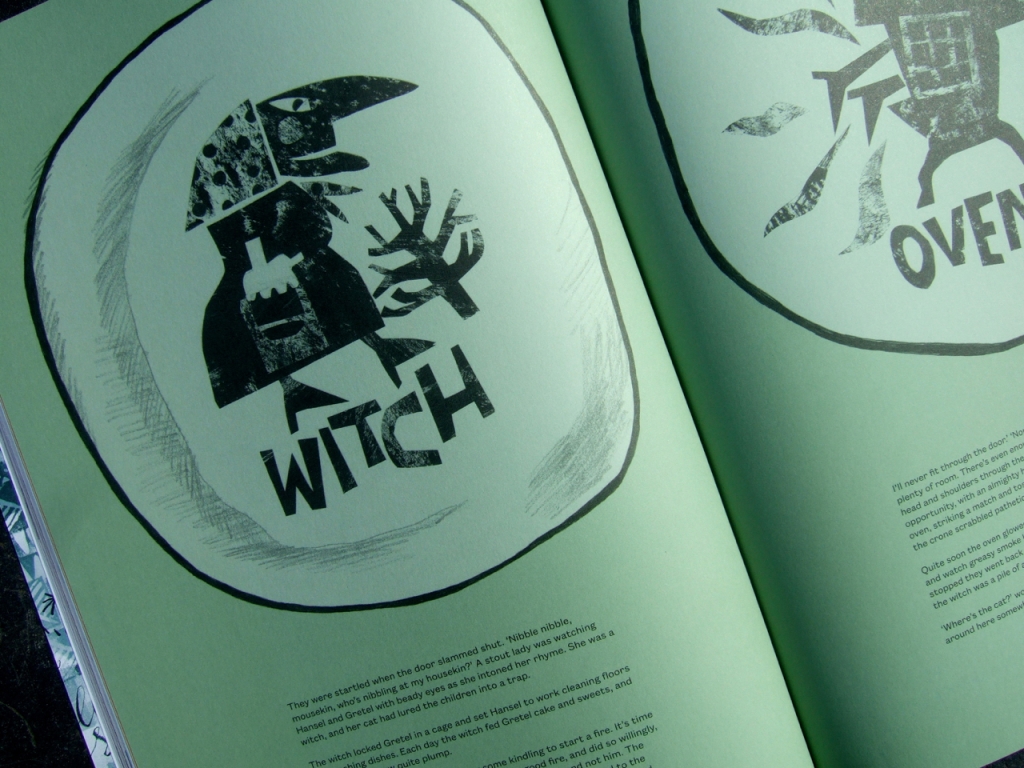

The plate designs, produced with hand-cut stencils reminiscent of European folk art, migrated from Clive’s kitchen shelves in 2014 when he adapted them into a series of illustrations for Random Spectacular magazine. After a passing comment at social media that he would like to expand the magazine piece into a picture book, Random Spectacular agreed to publish one. Clive envisioned a dark tale, one that asked difficult questions: “What happens to children who kill? What effect will it have on them?”

The character design of the siblings was vital to telling their story: “The children that I designed right at the start were really simple. There was a touch of St Trinian’s to them: short and pod-like with skinny arms and legs and dressed in school uniforms. Though caricatured there was a tenderness and bewilderment to them that was touching. Hansel is incredibly passive throughout, a poor lost puppy. Gretel appears meek, though later manifests an awesome inner Ninja.”

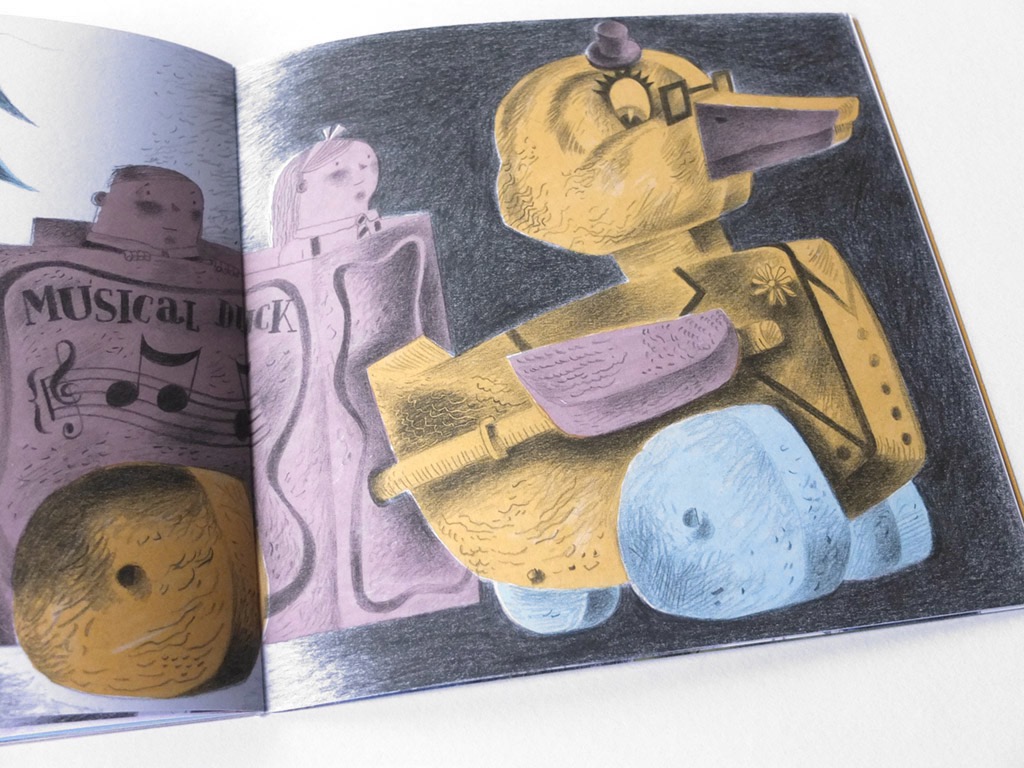

Alongside the cast of characters appear occasional motifs drawn from European toys and popular design ephemera that Clive has gathered over the years. “It’s not exactly a collection”, he explains, “but a loose gathering of objects that interest, intrigue and move me. Some inherited and some sought. I find that vintage toys worm their ways into my imagination and from there into my work.” While these elements represented a personal history, moments like Hansel and Gretel making their getaway with the aid of a duck based on a 1950s Fisher Price pull-toy, make Clive’s fantasy world uncannily familiar.

For the rendering of the book Clive made separations, a technique previously unfamiliar to him. Creating a drawing for each coloured layer of an illustration, the layers of drawings were then scanned and coloured digitally according to Pantone references he selected to create a sugared almond palette.

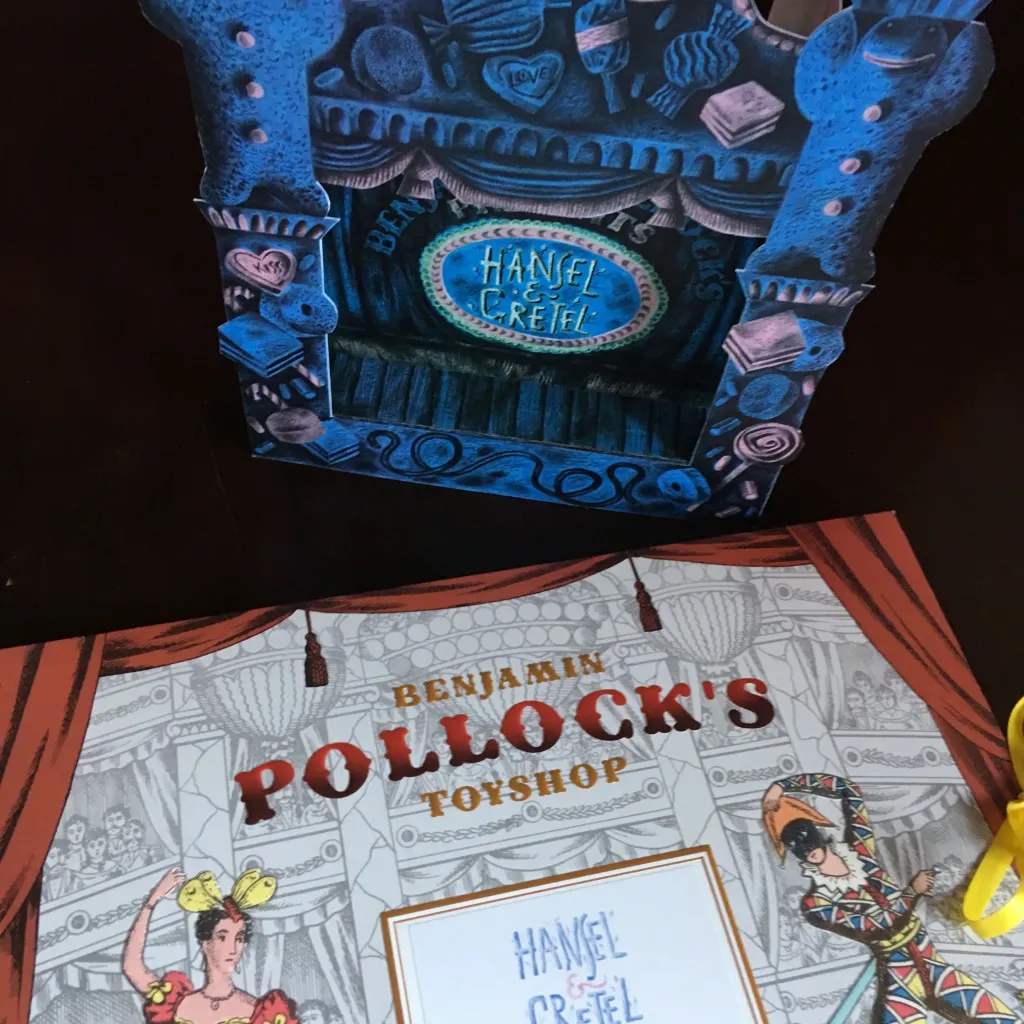

The Random Spectacular picture book was published in 2016, and the same year Clive was commissioned for another Hansel & Gretel project by Benjamin Pollock’s Toyshop in Covent Garden, which sells historic and contemporary cut-out-and-assemble toy theatres. The commission to create the Hansel & Gretel Toy Theatre resonated with Clive’s childhood: “As a boy I’d cut out, coloured in and performed Pollock’s productions on a home-made stage constructed from a cornflakes packet, and so this was a dream come true for me.”

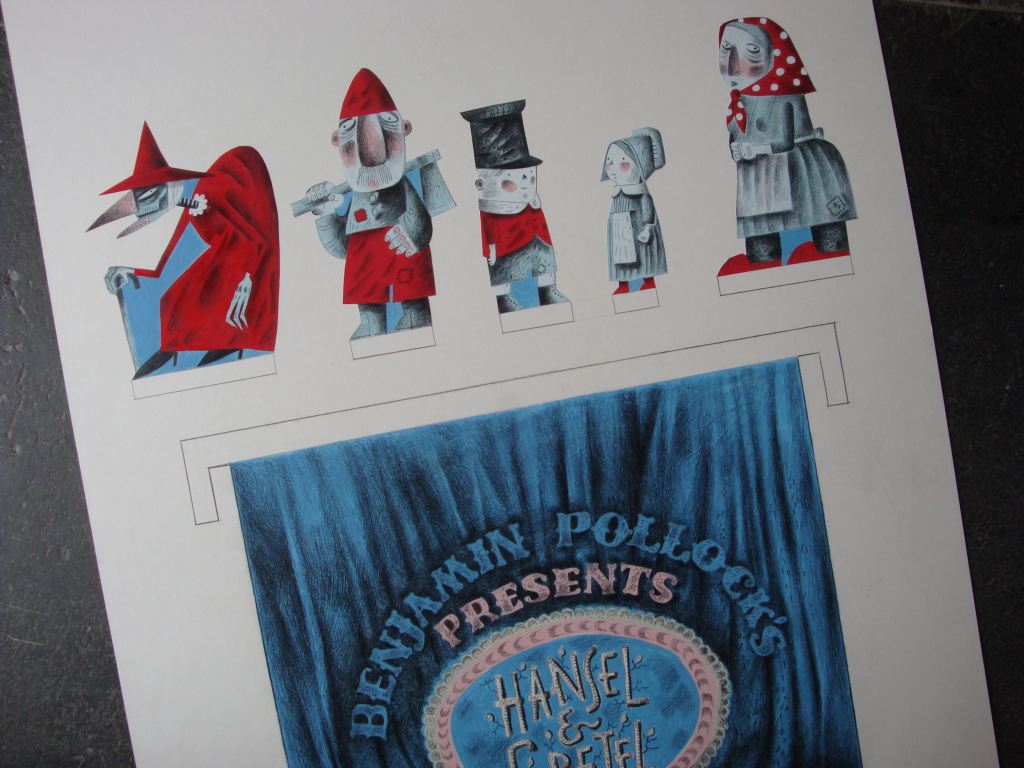

He initially suggested an adaptation of his Hansel & Gretel picture book, and while the Pollock’s project went on to incorporate some of the atmosphere of it, many of the more grotesque elements were considered “way too scary” for the toy theatre’s intended family audience. So Clive embarked on yet another adaptation of the story, re-fashioning it to create a meta- production in miniature, perhaps informed by his early career as a performer: The Pollock’s Hansel & Gretel Toy Theatre starts from the point where the picture book finishes. “Having survived the ordeal of the witch, the children leave home to make their way in the world. Arriving in the big city they’re picked up by a theatre impresario who promises fame and fortune if they sign a contact with him, and they duly end up starring in a pantomime version of their own story, though with most of the unpalatable bits edited out.

So no wicked mother ending up being murdered by their father, and a much tamer version of a witch who doesn’t have tentacles where her nose should be!” The performance takes place at the fictional ‘Theatre Royal, Jury Lane’, a play on word of London’s Theatre Royal in Drury Lane.

The Benjamin Pollock’s Hansel & Gretel Toy Theatre was published in 2017, and while light-hearted in tone, it retained some of the gothic horror of the picture book with its poisonous candy blues and pinks overlaid with a blanket of dark pencil hatching. The flatpack consists of a stage, proscenium arch, scenes, characters and props, along with a script and a poster to ‘advertise’ the production.

The following year, Clive’s Hansel & Gretel: a nightmare in eight scenes premiered on a life-size stage at the Cheltenham Music Festival. It subsequently toured the UK, finishing at the Barbican in London where a performance was recorded for broadcast Christmas week 2018 on BBC Radio 3.

For this his largest imagining of the story – a combination of live narration, music, animation and tabletop and shadow-screen puppetry – Clive collaborated with producer Kate Romano and the Goldfield Ensemble. The producer had originally visited Clive to discuss another project, but after seeing his Pollock’s designs suggested they make a music theatre production about the ill-fated brother and sister.

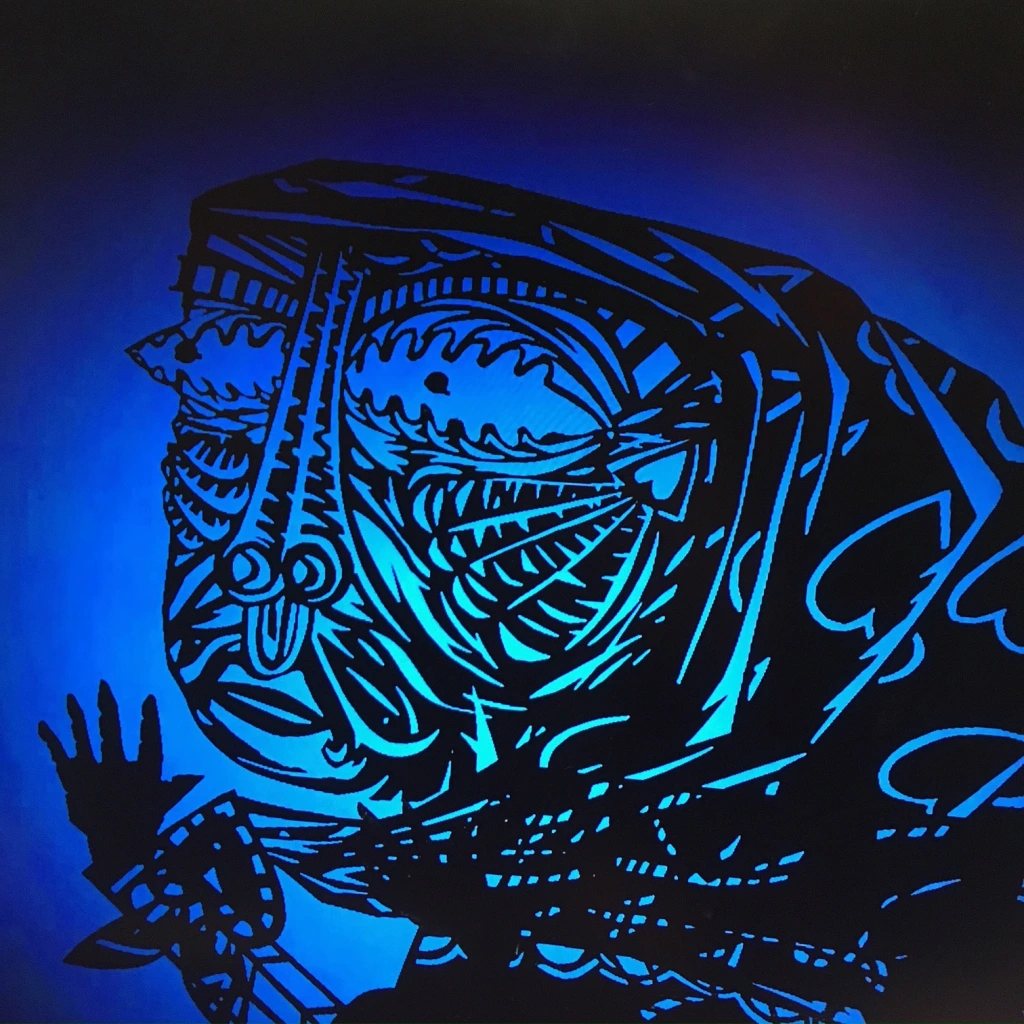

Clive recommended the producer enlist the poet Simon Armitage to write the libretto. Simon took the story in a completely different direction by placing the children into a contemporary context. “I think it was genius on Simon’s part to set the story in a conflict zone, and to rewrite the adults as loving parents fearful that their children might become casualties of war,” Clive says. “That changed everything for me in terms of how we relate to the family. They’re not dysfunctional, but find themselves in terrible circumstances.” The performance opened with animations of marching toy soldiers, which soon fall into the disarray of battle. Hansel and Gretel’s parents send their children away from this carnage in order to protect them.

However without their parents’ protection, they become enticed and ensnared by a witch. When she prepares to bathe them so they can be trafficked, Gretel fears that the hot water for the bath will be used for boiling them alive. “Everything that we see and hear is filtered through the overheated imaginations of the children who are full of fears and misunderstandings,” Clive explains.

“Everything in the production, from the predatory witch and her grubby icing-sugared cottage, to the layout of its bleak interior conjured from a doll’s house, is how they see things.”

Hansel and Gretel were puppets designed by Clive and made by Jan Zalud. “I needed the puppets to function at a different level to their picture book counterparts, and be fully up to the emotional requirements of Simon Armitage’s text, ” Clive says, and his designs evolved from research on the experiences of children in transit camps. This approach was not welcomed by the Goldfield ‘project team’, who reported his drawings made them think of children in concentration camps. “I stuck to my guns,” he remembers, “because I knew the direction was the right one.”

Only one Hansel and one Gretel puppet appeared in the production, so the design and execution created appropriately neutral expressions for the puppet’s faces onto which many thoughts could be projected by audiences. Because the streaming would see them much magnified on the screen, they’d need an innate grace of movement so the moments of tenderness and vulnerability would withstand close scrutiny.

Several collaborators were assembled and directed by Clive to realise the project. The composer Matt Kaner had come to it through Kate Romano. Clive invited Peter Lloyd to produce shadow puppets of the children’s parents and the witch, Pete Telfer, to film the animations to be projected onto the stage, and his regular collaborator and assistant Phil Cooper, to be in charge of the model sets and painted backgrounds for the puppets. Puppeteer Di Ford came to the project at Clive’s invitation having previously worked with him on the stage production of The Mare’s Tale, and after a puppeteer audition and workshop, Lizzie Wort joined the company. Costumier Oonagh Creighton Griffiths was brought in to dress the puppets.

As director of such a broad team, how did Clive retain his vision of the piece? His earlier career was in stage direction and choreography, and so he knows his choice of collaborators is vital. “I mostly work with people I know well and feel at ease with,” he says, “the team are my professional family. When we’re all pulling together there’s not really a hierarchy. Once briefed I trust them. Sometimes they bring me what I expect, and occasionally there are surprises. There need to be the possibilities that some elements may exceed my expectations or bring something entirely unanticipated.”

Clive’s own vintage toys played an important role onstage. One hundred year old German building blocks became the playthings of the children, and clockwork ‘pecking chickens’ stood in for the flock of birds that ate Hansel’s trail of breadcrumbs.

The chickens and a Russian clockwork ‘singing’ bird are also due to appear in Clive’s next iteration of the story: a richly illustrated edition of Simon Armitage’s libretto, produced by independent publisher Design for Today and due for release later this year.

“A toy,” Clive says, “can open your heart and make you remember what wonder feels like.” However his adoption of these tokens from the past is not an indulgence in nostalgia. “I’m not such a fool as to think that yesterday was better. I was there and it wasn’t! My explorations are all about objects being repositories of histories. They’re like radio dials, and if you twiddle them you ‘hear’ the past. That past can be anything, from sweet to despairing. It’s the focus that’s all important, and what the focus opens in the mind and heart.”

Olivia Ahmad, 2019.

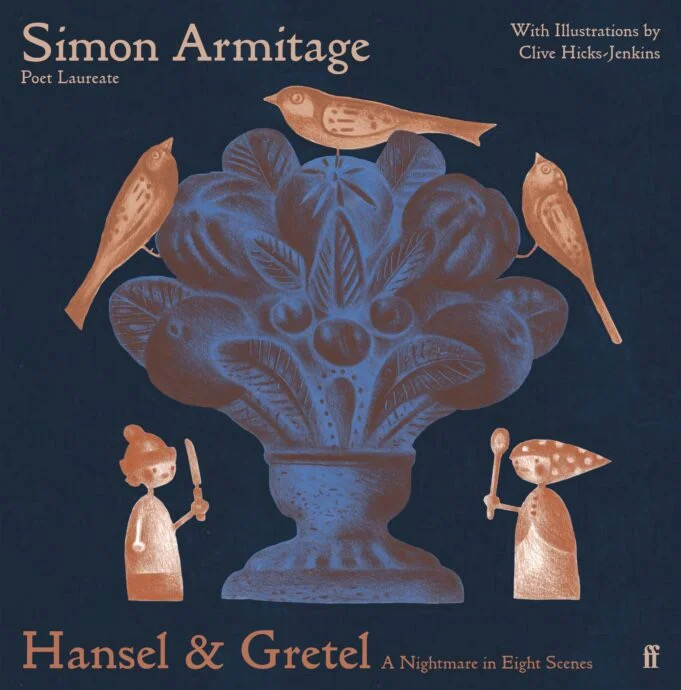

Hansel & Gretel was published subsequent to this article and in 2020 won the V&A Illustrated Book Award. It’s still available from the publisher at THIS LINK. In October a new hardback edition is due out from Faber & Faber.

Above, the 2019 Design for Today edition of Hansel & Gretel: a Nightmare in Eight Scenes, and below, the new edition forthcoming from Faber & Faber in October 2023.